| | | Birds are on the move! In most parts of the country, so are those of us who think its fun to get a sore neck looking up into the trees for warblers. But along with spectacular migrations, the decline of birds and their habitat continues. So, in this May issue of RCC’s Bird Watch and Wonder, we offer actions you can take to protect our avian friends, as well as victories achieved such as Virginia’s new regulation to stop the deaths of migrating birds by “incidental take.” There is also growing interest nationwide to improve the habitat of birds as in North Carolina’s famous barrier islands where Rachel Carson roamed and wrote. Urban and suburban environmentalists, too, are planting more and more pollinator and rain gardens to help butterflies and bees. But we are reminded that putting in shade trees like the mighty oak is not only good for butterflies, bees, and climate change, but for birds and other animals as well. This month, you’ll also find two original pieces by RCC’s Ross Feldner, along with a moving debut essay inspired by Rachel Carson from Zoe Wong, a gifted young RCC writer at Duke, who has studied whales and birds in two of Carson’s favorite locales – Bar Harbor, Maine and Beaufort, North Carolina.  The Great Dismal Swamp on the border of North Carolina and Virginia has long been a prime spot for birders to catch sight of the secretive Swainson’s Warbler. But Eric Sheppard revisits the history of the swamp in light of today’s efforts to understand our past and present through a lens of racial justice. The narrative of his enslaved ancestor, Moses Grandy, opens up our understanding of the enslaved and Indigenous people who lived there for centuries, those escaping from slavery and forming communities in the trackless wilderness, and what a superb knowledge of birds, animals, sky and stars they must have had long before white settlers ever dared set foot in the Dismal Swamp. The Great Dismal Swamp on the border of North Carolina and Virginia has long been a prime spot for birders to catch sight of the secretive Swainson’s Warbler. But Eric Sheppard revisits the history of the swamp in light of today’s efforts to understand our past and present through a lens of racial justice. The narrative of his enslaved ancestor, Moses Grandy, opens up our understanding of the enslaved and Indigenous people who lived there for centuries, those escaping from slavery and forming communities in the trackless wilderness, and what a superb knowledge of birds, animals, sky and stars they must have had long before white settlers ever dared set foot in the Dismal Swamp. Read on for book reviews, events and more. And be sure to send us your own short essays, photos, artwork, interesting sightings from backyard to bayou, or a note of what you’d like to see in our next issue of Bird Watch and Wonder. When not outside, you’ll find us at office@rachelcarsoncouncil.org | | BIRDS AND OUR WORLD Birds by the Billions: A Guide to Spring’s Avian Parade  For birders across the United States, it’s a rite of spring: heading out to woodlands and waterways to track down a favorite warbler, vireo, tanager or other bird, many of them migratory. For birders across the United States, it’s a rite of spring: heading out to woodlands and waterways to track down a favorite warbler, vireo, tanager or other bird, many of them migratory.

We asked five birding enthusiasts to give us a rundown on where to go and what bird species to look for in five regions of the United States. All you need are binoculars and a good field guide. The Midwest: Sandhill cranes, scarlet tanagers and more For me, the sound that signals spring is the rattling, staccato calls of gangly sandhill cranes winging overhead. For many years I volunteered for the International Crane Foundation’s Annual Midwest Crane Count, which placed me in a central Wisconsin marsh just outside Necedah National Wildlife Refuge before first light. There I sat shivering amid the stubborn patches of residual snow and brittle remains of the past year’s sedge grasses, listening intently for a bird call with the rhythmic texture of a spoon raking over a metal washboard. Read more Get Your Binoculars: The 25 Best National Parks for Birding  Find out which national park sites have the most bird species, with a highlight of what you might see at each place. Find out which national park sites have the most bird species, with a highlight of what you might see at each place.

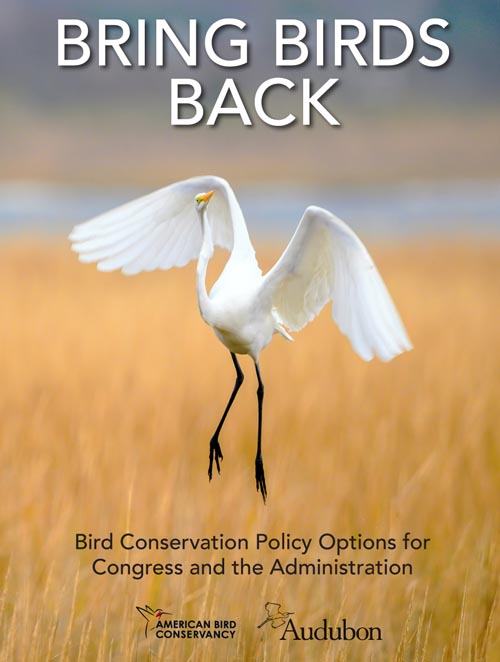

Millions of people visit national parks each year for the chance to spot wildlife, including such iconic species as black bears, bison, pronghorn and wolves — but wherever you go, you are virtually guaranteed to see birds. Each year, people spot more than 900 species of birds in the United States, and national parks are among the top viewing destinations. But which national parks have the most bird species? I wanted to know, so I dug into the data to find out. Avid birders all over the world use eBird to record their sightings and maintain lists of what they’ve seen. The eBird website collects all the information in a massive, searchable citizen science database showing bird sightings and other information. To find the national parks with the most kinds of birds, I went in and tallied up the recorded sightings for each of the 417 national parks units (yes, all 417!). A little bit about how this list works. First, birds sometimes wing themselves to unusual places, and birders love these rare sightings. Even if a particular species has only been spotted in a park once, it still counts for the park. Second, all these sightings are verified by eBird, which has pro birders that review sightings of rare birds in each state. So, we can trust these numbers. Read more | | | | ACTION/ADVOCACY Bring Birds Back Bird Conservation Policy Options for Congress and the Administration  The landmark study, “Decline of the North American Avifauna,” published in 2019 in the journal Science, found that bird populations have declined by close to 3 billion birds since 1970, representing a 29% overall decline in 50 years (Rosenberg et al. 2019). There are many historical and current causes of declining bird populations, including unregulated market hunting, habitat loss, direct mortality due to industrial hazards, predation by cats, by-catch in long-line and gillnet fisheries, building collisions, and invasive species (e.g., Trail 2006, Loss et al. 2013). In addition to these on-going threats, the harmful effects of climate change are increasingly manifest (e.g., Moller et al. 2010), and a recent Audubon report found that two-thirds of North America’s birds are gravely threatened by climate change (Wilsey et al. 2019). The landmark study, “Decline of the North American Avifauna,” published in 2019 in the journal Science, found that bird populations have declined by close to 3 billion birds since 1970, representing a 29% overall decline in 50 years (Rosenberg et al. 2019). There are many historical and current causes of declining bird populations, including unregulated market hunting, habitat loss, direct mortality due to industrial hazards, predation by cats, by-catch in long-line and gillnet fisheries, building collisions, and invasive species (e.g., Trail 2006, Loss et al. 2013). In addition to these on-going threats, the harmful effects of climate change are increasingly manifest (e.g., Moller et al. 2010), and a recent Audubon report found that two-thirds of North America’s birds are gravely threatened by climate change (Wilsey et al. 2019).

There is urgent need to address these and other threats so as to “avert continued biodiversity loss and potential collapse of the continental avifauna” (Rosenberg et al. 2019). Fortunately, the remarkable recovery of waterfowl populations, sustained now for decades, to say nothing of the endangered bird species returned from the brink of extinction, demonstrate that coordinated, sustained conservation action works. Just as there is no single cause of declining migratory bird populations, there is no single policy solution, program or approach that will suffice. Instead we need a suite of actions that foster on-the-ground protection, mitigation, and restoration of bird populations and the habitats they need to thrive. Click her to download PDF Virginia Approves Groundbreaking Migratory Bird Protection Regulation  A straightforward process will protect birds as major developments are planned. A straightforward process will protect birds as major developments are planned.

Media Contact: Jordan Rutter, ABC Director of Public Relations, 202-888-7472 jerutter@abcbirds.org | @JERutter

Expert Contact: Joel Merriman, ABC Bird-Smart Wind Energy Campaign Director, 202-888-7471 jmerriman@abcbirds.org

(Washington, D.C., March 19, 2021) Virginia's Department of Wildlife Resources has approved a groundbreaking new regulation, setting a major precedent for the protection of migratory birds. The approved regulation aims to reduce the loss of migratory birds from “incidental take” — the unintended but predictable killing of birds. “The new system is the first of its kind in the country, providing a model for other states to follow,” says Joel Merriman, American Bird Conservancy's (ABC's) Bird-Smart Wind Energy Campaign Director. “The conservation benefits are clear, and the rule also provides clarity to industry on the circumstances under which unavoidable incidental take is allowed. This all occurs through the use of established industry-specific best practices aimed at reducing impacts.” Read more Legislation To Reduce Bird Collisions Reintroduced In The U.S. House Of Representatives  Media Contact: Jordan Rutter, Director of Public Relations, 202-888-7472 jerutter@abcbirds.org | @JERutter Media Contact: Jordan Rutter, Director of Public Relations, 202-888-7472 jerutter@abcbirds.org | @JERutter

Expert Contact: Dr. Christine Sheppard, Director, Glass Collisions Program, 914-261-8277 csheppard@abcbirds.org

(Washington, D.C., March 17, 2021) American Bird Conservancy (ABC) applauds U.S. Rep. Mike Quigley (D-IL) and Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) for reintroducing H.R. 919 – Bird-Safe Buildings Act today. This bipartisan bill is designed to reduce bird mortality by calling for federal buildings to incorporate bird-safe materials and design features. As many as 1 billion birds a year die in collisions with buildings in the United States alone. Congressman Mike Quigley has been the driving force behind this bipartisan legislation for more than a decade. “As more and more cities across the country, including Chicago and just this week Philadelphia, adopt policies and practices to prevent bird-building collisions, the federal government must step up and do its share,” said Congressman Quigley. “We can help set an example for the country and the world and prove that bird-safe building design is cheap, easy, and effective. Read more | | | | BIRDS • ECOLOGY The Oak Tree – A Bird Sanctuary? - Bob Musil  We associate birds with particular habitats and many with certain trees — Blue-winged Warblers in locusts, kinglets in hemlocks, Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in longleaf pines, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers on birches. And these days, many of us are putting native plants in our yards and gardens to attract and help pollinators like bees or butterflies. We associate birds with particular habitats and many with certain trees — Blue-winged Warblers in locusts, kinglets in hemlocks, Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in longleaf pines, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers on birches. And these days, many of us are putting native plants in our yards and gardens to attract and help pollinators like bees or butterflies.

My parents would have been puzzled by the clover and buttercups I let sprout in my lawn, or the milkweed, joe pye, goldenrod, and other weedy stuff that filled the fields I roamed in as a boy before development paved almost all of Long Island. My parents would have been puzzled by the clover and buttercups I let sprout in my lawn, or the milkweed, joe pye, goldenrod, and other weedy stuff that filled the fields I roamed in as a boy before development paved almost all of Long Island.

But who plants oak trees these days? They are the stuff of poetry and history, of yesteryear, as in “old oaken bucket.” So, I should admit that I have carefully tended a healthy red oak sapling in my garden since a squirrel put it there nearly 10 years ago despite the mature tulip poplars, pin oaks, some dogwoods, a hawthorn, a huge specimen Southern magnolia, and a neighbor’s massive beech tree that already create sylvan shade and leaf litter in my modest suburban homestead. But I love oaks because I love shade and hate heat and humidity (and air conditioning bills) in sunny, sweaty Bethesda. And I know they sequester carbon dioxide and combat global warming. But who plants oak trees these days? They are the stuff of poetry and history, of yesteryear, as in “old oaken bucket.” So, I should admit that I have carefully tended a healthy red oak sapling in my garden since a squirrel put it there nearly 10 years ago despite the mature tulip poplars, pin oaks, some dogwoods, a hawthorn, a huge specimen Southern magnolia, and a neighbor’s massive beech tree that already create sylvan shade and leaf litter in my modest suburban homestead. But I love oaks because I love shade and hate heat and humidity (and air conditioning bills) in sunny, sweaty Bethesda. And I know they sequester carbon dioxide and combat global warming.  Yet it took Adrian Higgins, the gardening columnist of the Washington Post, to remind me and convince me that solid, staid, stately oak trees are good for the pollinators and the birds as well. Their acorns feed turkeys, woodpeckers, crows, titmice and, of course Blue Jays. But drawing on native plant guru Doug Tallemy’s new book, Quercus, a kind of ode to oaks, Higgins discovered that oaks support more forms of life than any other tree genus in America and that they are critical to migrating birds who eat the caterpillars of the many moths and butterflies that feast on young oak leaves. If you love butterflies and birds, you should plant some oaks. Adrian Higgins can explain how and why. Read more Yet it took Adrian Higgins, the gardening columnist of the Washington Post, to remind me and convince me that solid, staid, stately oak trees are good for the pollinators and the birds as well. Their acorns feed turkeys, woodpeckers, crows, titmice and, of course Blue Jays. But drawing on native plant guru Doug Tallemy’s new book, Quercus, a kind of ode to oaks, Higgins discovered that oaks support more forms of life than any other tree genus in America and that they are critical to migrating birds who eat the caterpillars of the many moths and butterflies that feast on young oak leaves. If you love butterflies and birds, you should plant some oaks. Adrian Higgins can explain how and why. Read more One of North Carolina’s Last Unprotected Barrier Islands to be Conserved  Conservation groups, family landowners rally to conserve Hutaff Island. Conservation groups, family landowners rally to conserve Hutaff Island.

Hutaff Island, one of North Carolina’s last privately owned undeveloped barrier islands, will be conserved forever thanks to a partnership between Audubon North Carolina, NC Coastal Land Trust, and the Hutaff/McEachern family, funded by conservation philanthropist Tim Sweeney. Hutaff is a 2-mile long ribbon of pristine beach and saltmarsh located between Lea Island and Topsail Beach to the north and Figure 8 Island to the south. Conserving this wild and uninhabited place in perpetuity will keep the island’s natural inlets and dynamic ecosystems intact, providing critical habitat for sea turtles, vulnerable beach-nesting birds like Black Skimmers, and a host of other rare and threatened wildlife. "Hutaff Island is a rare gem on the North Carolina coast. It’s one of the last, best examples of a natural barrier island with dynamic dunes and productive saltmarsh," said Walker Golder, Executive Director of the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust. "We are so very grateful to the Hutaff/McEachern family for their commitment to conserving the island forever and to the partnership that brought us to this important day." Read more | | | | BIRD LORE Our Deep Connection to Birds  We all know songs that mention birds, from “Bye Bye Blackbird”, first published in 1924 by Jerome H. Remick, to the Beatles “Blackbird” from their 1968 White Album. Birds in song often symbolize something human, something we relate to that is often uplifting, even bordering on the spiritual. From ancient times to the pulsating present, birds are deeply ingrained in human culture. We all know songs that mention birds, from “Bye Bye Blackbird”, first published in 1924 by Jerome H. Remick, to the Beatles “Blackbird” from their 1968 White Album. Birds in song often symbolize something human, something we relate to that is often uplifting, even bordering on the spiritual. From ancient times to the pulsating present, birds are deeply ingrained in human culture.

We look to birds as symbols of freedom, or the opposite when the bird is caged, or cunning in the “Crow and the Pitcher,” an Aesop fable where the crow figures out how to get a drink of water from a half-filled pitcher by dropping in pebbles until the water level is high enough for it to drink. They can represent rebirth like the mythical Phoenix that rises from the ashes. Or birds may represent omens of death as in the superstition that if you see 5 crows, sickness will follow; see 6 crows and death will come. Read more Expect the Unexpected  Having been an avid birder since my early teens I now find new sightings few and far between. I haven’t experienced the thrill of seeing a new species of bird and marking it off on my “life list” in years and yet… Having been an avid birder since my early teens I now find new sightings few and far between. I haven’t experienced the thrill of seeing a new species of bird and marking it off on my “life list” in years and yet…

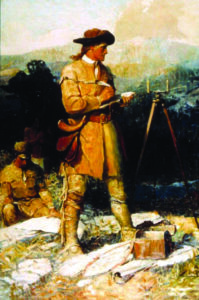

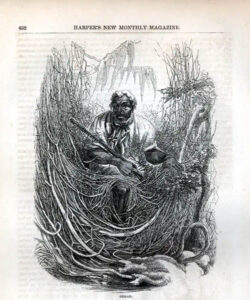

On a recent weekend on a local nature trail the unexpected happened. My wife and I were enjoying a beautiful day of hiking, stopping now and then to investigate which bird was doing the singing or flitting through the brush. Nothing eventful so far. We reached a rise on the trail that leads to a walk around a very large pond when I saw a trio of Eastern Phoebes sitting in plain view. This dapper bird perches and scans for insects often keeping up a running series of sharp chirps. We watch as they take flight again and again, catching insects on the wing, which I always find both fascinating and almost unbelievable considering how difficult it must be. I can hardly get a housefly with a swatter. Read more The Last It Ever Saw  On a crisp morning in September, a bird dove towards the ocean. It was a gannet, pure white with a baby blue beak tapering to a fine point, wings and tail tipped in black. Its over-large wings were tucked in close, acting as twin rudders to direct the head-first plunge. But as the gannet neared the waves, it stretched its wings and flattened them against its body, becoming a torpedo painted with a pale blue tip and black tailfins, custom-made to spear deep into the water. The silver herring below had no chance, for how could it defend against an enemy that at one moment wheels innocently in the sky, and within half a second reappears underwater to gulp down its prey? On a crisp morning in September, a bird dove towards the ocean. It was a gannet, pure white with a baby blue beak tapering to a fine point, wings and tail tipped in black. Its over-large wings were tucked in close, acting as twin rudders to direct the head-first plunge. But as the gannet neared the waves, it stretched its wings and flattened them against its body, becoming a torpedo painted with a pale blue tip and black tailfins, custom-made to spear deep into the water. The silver herring below had no chance, for how could it defend against an enemy that at one moment wheels innocently in the sky, and within half a second reappears underwater to gulp down its prey? The gannet’s densely-woven feathers insulated it from the chilly waters of the Gulf of Maine, and as it bobbed back up to the surface amidst the first rays of sunlight, it shivered, sending salty droplets into a rainbow arc above its head. Nearby, an uneven fingertip of land peeked above the waves. The island known as Mount Desert Rock was large enough to host a lonely lighthouse and a small, weather-beaten cabin, but too small and rocky to allow any greenness aside from a few scraggly bushes that huddled in the cabin’s lee. Read more Free as a Bird: Prime Birding and Black Heritage at the Great Dismal Swamp - Bob Musil   My old copy of Claudia Wild’s classic Finding Birds in the National Capital Area says that the southeast corner of Virginia is best known to birders for its Swainson’s Warblers and that the Great Dismal Swamp NWR, where you can see them, is a “famous swamp, surveyed by George Washington.” That is quite true, and the Great Dismal Swamp is indeed a great spot for birding. By mid-April, for instance, the on-line eBird Tracker maintained by the refuge had already listed 17 gorgeous Prothonotary Warblers in a single day. The refuge is accessible by car, bicycle, or on foot with boardwalks that will take you through the swamp right to the birds. You can learn that The Great Dismal Swamp NWR is the largest intact remnant of a vast habitat that once covered more than one million acres of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. My old copy of Claudia Wild’s classic Finding Birds in the National Capital Area says that the southeast corner of Virginia is best known to birders for its Swainson’s Warblers and that the Great Dismal Swamp NWR, where you can see them, is a “famous swamp, surveyed by George Washington.” That is quite true, and the Great Dismal Swamp is indeed a great spot for birding. By mid-April, for instance, the on-line eBird Tracker maintained by the refuge had already listed 17 gorgeous Prothonotary Warblers in a single day. The refuge is accessible by car, bicycle, or on foot with boardwalks that will take you through the swamp right to the birds. You can learn that The Great Dismal Swamp NWR is the largest intact remnant of a vast habitat that once covered more than one million acres of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina.  But what Claudia Wild and other birders and naturalists who wrote long ago did not know or mention is that George Washington did indeed survey the Great Dismal Swamp, but with an eye to acquiring and developing it for slave plantations. Nor was it widely known that the swamp was home to the Nansemond, Meherrin and Nottoway tribes and had also been a haven for runaway slaves even before the area was explored by white colonists in the 18thcentury. But what Claudia Wild and other birders and naturalists who wrote long ago did not know or mention is that George Washington did indeed survey the Great Dismal Swamp, but with an eye to acquiring and developing it for slave plantations. Nor was it widely known that the swamp was home to the Nansemond, Meherrin and Nottoway tribes and had also been a haven for runaway slaves even before the area was explored by white colonists in the 18thcentury.

That the Great Dismal Swamp and its birds, animals and their habitat has been preserved is a lasting testament to early conservationists. It could have been drained, filled in and developed for condominiums and cars long ago. But Eric Sheppard, whose ancestor, Moses Grandy, wrote an important slave narrative about the swamp, is pushing along with others to have the Great Dismal Swamp preserved as a National Heritage Area to preserve and promote the areas distinctive African American and Indigenous history. That would be a fitting form of conservation for our time. Read more That the Great Dismal Swamp and its birds, animals and their habitat has been preserved is a lasting testament to early conservationists. It could have been drained, filled in and developed for condominiums and cars long ago. But Eric Sheppard, whose ancestor, Moses Grandy, wrote an important slave narrative about the swamp, is pushing along with others to have the Great Dismal Swamp preserved as a National Heritage Area to preserve and promote the areas distinctive African American and Indigenous history. That would be a fitting form of conservation for our time. Read more Four Winged Poems From National Poetry Month  THIS TIME OF YEAR, the birds catch my attention and hold it. The robins are back, or maybe they’re just bolder. I see them most in this early spring season, when the worms are warming up out of the soil. The goldfinches are muted still, their diets not yet offering the delights that turn their plumage bright. And the mourning doves are crying all day long. THIS TIME OF YEAR, the birds catch my attention and hold it. The robins are back, or maybe they’re just bolder. I see them most in this early spring season, when the worms are warming up out of the soil. The goldfinches are muted still, their diets not yet offering the delights that turn their plumage bright. And the mourning doves are crying all day long.

I love how focused I can be on the birds right now, without the distraction of foliage to block me from seeing them clearly. I love the way that watching them helps slow me down. This time of year, life can start to seem crowded and hectic. The school term is almost over, though there is still much work to complete. Longer days seem to come with more demands. I am grateful, then, for the birds. Grateful for the nuthatches who duck behind the arborvitae then pop out again with a precise attention honed, perhaps, by hunger. Grateful for the pair of finches whose coupled flights to the feeder entertain us every morning. They offer new ways of seeing the world. Read more How Mrs. Edge Saved the Birds  Suffragist Rosalie Barrow Edge founded the world's first refuge for birds of prey. (Illustration by Julia Breckenreid). Suffragist Rosalie Barrow Edge founded the world's first refuge for birds of prey. (Illustration by Julia Breckenreid).

Meet a forgotten hero of our natural world whose brave campaign to protect birds charted a new course for the environmental movement.

One frosty October morning, I climbed a winding mile-long path to the North Lookout at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Eastern Pennsylvania. Laurie Goodrich, the director of conservation science, was already on watch, staring down the ridge as a chilly wind swept in from the northwest. She has been scanning this horizon since 1984, and the view is as familiar to her as an old friend.

“Bird coming in, naked eye, slope of Five,” Goodrich said to her assistant, using a long-established nickname for a distant rise. A sharp-shinned hawk popped up from the valley below, racing by just above our heads. Another followed, then two more. A Cooper’s hawk swooped close, taking a swipe at the great horned-owl decoy perched on a wooden pole nearby. Goodrich seemed to be looking everywhere at once, calmly calling out numbers and species names as she greeted arriving visitors. Read more | | | |  BIRD FINDINGS For the Birds: Waxwing Sighting Results in Learning Something New, by Chris Bosak  I had hobbled almost all the way from the car to the entrance of work when I noticed a flock of cedar waxwings picking off leftover berries in a nearby tree. I had hobbled almost all the way from the car to the entrance of work when I noticed a flock of cedar waxwings picking off leftover berries in a nearby tree.

Even with the persistent tendinitis in my feet acting up, I made my way back to the car to grab the camera. Usually, in situations like this the camera is sitting at home, but this time I was prepared for the unexpected. Cedar waxwings, in my experience anyway, are always unexpected. They are fairly nomadic, and it’s hard to go out looking specifically for them. But they appear now and then and it’s always a thrill to see them.

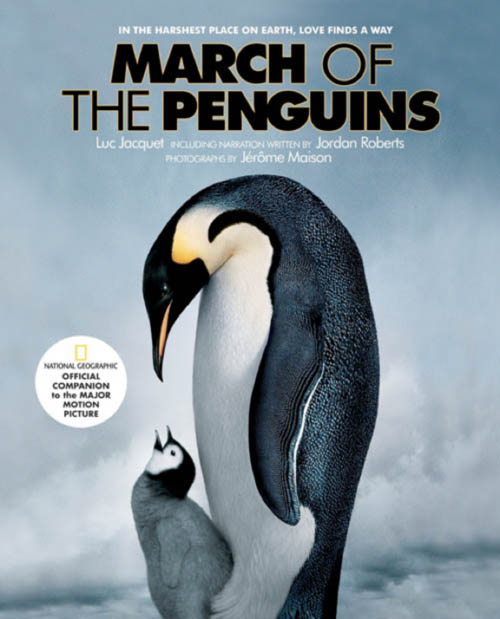

I retrieved the camera and hobbled back through the parking lot to the tree in question. Of course, the tree was empty when I got back as the waxwings had taken off for parts unknown. Things like that have happened far more than I’d like to admit, so I just reported for duty and got to work. Thankfully, the window from my office has a view of that tree, and about 15 minutes later the waxwings were back in force. I slowly made my way back outside and, as is often the case with waxwings, they obliged by going about their business and not minding the click of the camera. Read more | | | |  March of the Penguins (2005)  Although this film is now over 15 years old it’s subjects are timeless and riveting. The March of the Penguins is one of the highest rated documentaries of all time. You will go on an epic journey following the lives, struggles, and accomplishments of Emperor Penguins. Although this film is now over 15 years old it’s subjects are timeless and riveting. The March of the Penguins is one of the highest rated documentaries of all time. You will go on an epic journey following the lives, struggles, and accomplishments of Emperor Penguins.

At the end of each Antarctic summer, the emperor penguins of the South Pole journey to their traditional breeding grounds in a fascinating mating ritual that is captured in this documentary by fearless filmmaker Luc Jacquet. The follows the penguin’s journey across frozen tundra proves which turns out to be the simplest part of the ritual.

After the egg is hatched, the female must delicately transfer it to the male and make her way back to the distant sea to nourish herself and bring back food to her newborn chick. The fact that these birds do this every year is one of nature’s miraacles. This film rates 94% at Rotten Tomatoes. Watch the trailer here | | | |  | BOOK REVIEWS When the Hidden World of Birds is First Revealed By Jeff and Allison Wells  The pure joy of discovery. As children we often felt that joy, as we found something we had never seen or learned about something wondrous that we had only dreamed of or heard stories about. Sometimes it was something so new that we couldn’t even fathom it and were left puzzling. Those of us who were fortunate enough to spend time around a wise, loving, and supportive elder might have had the experience of learning some of these wondrous things from them. The pure joy of discovery. As children we often felt that joy, as we found something we had never seen or learned about something wondrous that we had only dreamed of or heard stories about. Sometimes it was something so new that we couldn’t even fathom it and were left puzzling. Those of us who were fortunate enough to spend time around a wise, loving, and supportive elder might have had the experience of learning some of these wondrous things from them.

Even now we can remember the excitement we felt in our first-ever discovery of a bird that we had seen pictured in our old Peterson field guide that we had inherited from our parents or grandparents. That first yellow-rumped warbler or brown creeper or hermit thrush or rose-breasted grosbeak, or any of the many other first birds, seemed truly magical. It was as though our minds couldn’t fully grasp that the paintings in the field guide were depictions of truly living entities that flew, and hopped, and called, and sang. So when we would see one of these birds bursting with life, it was as though we had seen a unicorn or a wizard from a mystical fairy tale. We can clearly remember that pure burst of joy we experienced with each glimpse into a world that we had never known existed. Now, it’s harder for us to experience that same feeling here in Maine where we have seen and know well a lot about most of the bird species that regularly occur here. That’s not to say that we still don’t find endless fascination and satisfaction as we watch and learn more about even the most familiar of birds. We do. But there is one way to recapture the first-time joy of seeing a bird species even when you’ve seen it many times before. Read more | | | | | |  The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. | | | |  Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. | | | | | | | | | | | |