| | |  May marked a month of migration for bird species across the United States. As they escaped the cold winter months and completed their journeys to breeding grounds in early June, stories of lively birds, birders, and activism flooded the news. One prevalent theme in these stories was the diversification of birding. As you read through this issue of the RCC’s Bird Watch and Wonder newsletter, look out for stories about historically unnamed women receiving the recognition they deserve, the creations of young people as they enter the world of birding, and events for Black birders who are fighting for equal access to nature and beloved species. Learn about birding events that are for everybody and every body and about the connection between bird and human migration. May marked a month of migration for bird species across the United States. As they escaped the cold winter months and completed their journeys to breeding grounds in early June, stories of lively birds, birders, and activism flooded the news. One prevalent theme in these stories was the diversification of birding. As you read through this issue of the RCC’s Bird Watch and Wonder newsletter, look out for stories about historically unnamed women receiving the recognition they deserve, the creations of young people as they enter the world of birding, and events for Black birders who are fighting for equal access to nature and beloved species. Learn about birding events that are for everybody and every body and about the connection between bird and human migration.  As the push for diversity and equity strengthens, so does the movement to protect birds and their ecosystems. The Biden administration continues to reverse actions taken by the Trump administration to weaken protections on endangered species and habitats. But one question that remains is this: how can we do more? From dimming skylines to protecting wetlands, this issue of BWW delves into ways we can save the birds we love, especially the 66% of North American birds at risk from extinction due to climate change. Fortunately, there are plenty of ways to help, such as talking to our communities about becoming bird-friendly and urging our representatives to recover America’s wildlife. As the push for diversity and equity strengthens, so does the movement to protect birds and their ecosystems. The Biden administration continues to reverse actions taken by the Trump administration to weaken protections on endangered species and habitats. But one question that remains is this: how can we do more? From dimming skylines to protecting wetlands, this issue of BWW delves into ways we can save the birds we love, especially the 66% of North American birds at risk from extinction due to climate change. Fortunately, there are plenty of ways to help, such as talking to our communities about becoming bird-friendly and urging our representatives to recover America’s wildlife. For more bird news, films, books, and events, continue reading the June issue of Bird Watch and Wonder. When not outside, you’ll find us at office@rachelcarsoncouncil.org | |  BIRD FINDINGS He Wasn’t a Bird Person. Then a Hawk Built a Nest on His Fire Escape.  Life, death, renewal and social media ensued. Life, death, renewal and social media ensued.

Michael Palma Mir’s first encounter with the hawk was not auspicious. Around the first of March, he noticed it outside his West Harlem apartment.

In his 57 years living there, Mr. Palma Mir had never seen anything like this beautiful bird, a killer. He grabbed his camera and stuck his head out the window for a better shot. The next thing he knew, it was right there. “It was three feet away from me and coming in real fast,” he said. “All I saw were the talons coming right at my head.” He yanked his head back inside and slammed the window, never expecting to see the bird again. He was wrong. The hawk returned, again and again, turning Mr. Palma Mir’s fire escape — six stories above a nonbucolic corner of upper Broadway — into a nest and a soap opera for social media. The saga of Billy and Lilly, two red-tailed hawks that Mr. Palma Mir named after his parents, is one of regeneration and joy, with a tinge of sadness and some dead rat carcasses. Read more Bird of the Month - Eastern Phoebe  SCIENTIFIC NAME: Sayornis phoebe SCIENTIFIC NAME: Sayornis phoebe

POPULATION: 33 million

TREND: Increasing

HABITAT: Breeds and winters in open woodland, farmland, and suburbs, often near water

The Eastern Phoebe may lack the visual appeal of a Northern Cardinal or Scarlet Tanager, but this drab little flycatcher is just as popular among birdwatchers. It's easy to identify, both for its onomatopoeic calls and tail-wagging habit. And it's often in view: An Eastern Phoebe pair will often nest on or near human-made structures. The species is a reliable herald of spring, as one of the earliest songbirds to return to eastern U.S. breeding areas. The unusual spelling of the Eastern Phoebe's name harkens back to Greek mythology: Phoebe was the daughter of “Earth” (Gaea) and “Sky” (Uranus), another fitting tie-in to this outdoor neighbor to many. Famed ornithologist and artist John James Audubon was particularly familiar with and fond of the Eastern Phoebe, which he called the "Pewee Flycatcher." The species nested around his home in Mill Grove, Pennsylvania, where Audubon courted his neighbor and future wife Lucy Bakewell. In 1803, Audubon carried out the first bird-banding experiment in America at Mill Grove, when he attached silver thread to the legs of Eastern Phoebe nestlings before they migrated. The next spring, he recaptured two of the marked phoebes, which had returned to his property. From that time until today, ornithologists have employed bird banding to track birds' migratory movements and to ensure accurate counts of their populations. Read more 'I bird because I like doing it:' The Color of Bird Watching and Why Diversity is Needed Black Birders Week runs from May 30th to June5th.  This week starts Black Birders Week to highlight Black nature enthusiasts, to show what unique challenges they face and why it’s important for Black and brown people to be active in talks about conservation. This week starts Black Birders Week to highlight Black nature enthusiasts, to show what unique challenges they face and why it’s important for Black and brown people to be active in talks about conservation.

Birds come in so many beautiful colors, so it’s ironic that the world of birding and ornithology is void of color. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, only 4% of birders are Black. “I bird because I like doing it, and I wanna make sure that everybody feels like this is something that they can do,” says Tykee James of DC Audubon Society. James' favorite bird is the belted kingfisher and he says it is what got him started in birdwatching. “It's something that connected me to my community," he said. “I realized being present for that connected me to the environmental movement.” James now works giving bird walks and educating people on our local natural resource Read more | | | | EVENTS #BLACKBIRDERSWEEK2021 Get Ready!!  After the global success of its inaugural year, #BlackBirdersWeek returns Sunday, May 30 through Saturday, June 5, 2021. After the global success of its inaugural year, #BlackBirdersWeek returns Sunday, May 30 through Saturday, June 5, 2021.

This year’s event will showcase the many unique ways Black people connect in the outdoors.

The week’s lineup includes nationwide birding events, live streamed panel discussions, and daily interactive themes. In partnership with The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Bird Collective, US Fish Wildlife Service, National Wildlife Federation, Tucson Audubon Society, and more, #BlackBirdersWeek2021 is taking flight! Read more Birding Festivals and Events  A great way to enjoy bird watching is by going to festivals—they’re organized to get you to great birding spots at a great time of year, and they’re a great way to meet people. Experts and locals help you see more birds, and you’ll meet other visitors who share your hobby. While you’re there, keep an eye out for Cornell Lab representatives, as we do attend several festivals each year. A great way to enjoy bird watching is by going to festivals—they’re organized to get you to great birding spots at a great time of year, and they’re a great way to meet people. Experts and locals help you see more birds, and you’ll meet other visitors who share your hobby. While you’re there, keep an eye out for Cornell Lab representatives, as we do attend several festivals each year.

Adirondack Boreal Birding Festival - June 10 - June 13

https://www.adirondackexperience.com/

Hamiilton County, New York, Lake Pleasant, NY 12108 United States Rangeley Birding Festival - June 11 - June 13

http://www.rlht.org/birding-festival

Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust, 2424 Main Street , Rangeley, ME 04970 United States Mono Basin Bird Chautauqua - June 18 - June 20

http://birdchautauqua.org/

Lee Vining, California, 296 Mattly Ave., Lee Vining, CA United States Click here to see all the festivals | | | | BIRD LORE Patience is a Virtue (Especially with birding) “I find if I just sit down and think, the solution presents itself.” Henry Jones, father of Indiana Jones from the movie “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.”  In 1969, my junior year of high school, me and two of my friends had all become ravenous birders. Out every day searching for new species, studying our field guides and many afternoons playing “hangman” using bird names as a memory aid. We were as they say, “All in.” That same year we decided to take a field trip. A long field trip in search of the uncommon Pileated woodpecker. Although fairly common in the eastern US this mighty bird of great dimensions and a powerful jackhammer of a beak was a rare sighting in northern California where I was living at the time in Palo Alto. We planned a quest north and to keep going until we found the great one. In 1969, my junior year of high school, me and two of my friends had all become ravenous birders. Out every day searching for new species, studying our field guides and many afternoons playing “hangman” using bird names as a memory aid. We were as they say, “All in.” That same year we decided to take a field trip. A long field trip in search of the uncommon Pileated woodpecker. Although fairly common in the eastern US this mighty bird of great dimensions and a powerful jackhammer of a beak was a rare sighting in northern California where I was living at the time in Palo Alto. We planned a quest north and to keep going until we found the great one. The Pileated Woodpecker is one most striking forest birds on the continent. Approximately the size of a crow with bold black and white stripes down the neck and a flaming-red crest. This unique bird hammers rectangular holes in trees in search of their main prey, carpenter ants. Thanks Pileated Woodpecker! Their nest holes often offer crucial shelter to many species including swifts, owls, ducks and bats. Read more Migration Lessons From Long Point Restlessness defines the spectacle of migration and those who study it.  Not long after college, I found myself at Point Reyes Bird Observatory (now Point Blue Conservation Science) working in the national seashore by the same name, right on the Pacific. My comrades at the Palomarin Field Station were itinerant field biologists and birders like me. Ostensibly, we were moving from field job to field job to gain experience and build our resumés so that we could one day get real jobs — full-time ones that, well, actually paid. Or at least this is what we told our parents, all of whom, I assure you, were concerned about our chosen career paths. Not long after college, I found myself at Point Reyes Bird Observatory (now Point Blue Conservation Science) working in the national seashore by the same name, right on the Pacific. My comrades at the Palomarin Field Station were itinerant field biologists and birders like me. Ostensibly, we were moving from field job to field job to gain experience and build our resumés so that we could one day get real jobs — full-time ones that, well, actually paid. Or at least this is what we told our parents, all of whom, I assure you, were concerned about our chosen career paths.

As we filled our days together netting and banding birds of the northern California coastal scrub, we'd sometimes fantasize about our next adventures. Maybe Southeast Farallon Island, just out of sight in the fog offshore; or Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania; Cape May, New Jersey; Eilat, Israel; Falsterbo, Sweden; or Fair Isle, United Kingdom? It seemed that we, like migratory birds, felt a certain kind of restlessness. Read more Who's Who These owls may wear the same game face, but when it comes to personality, they’re as different as day and night.  It’s not easy to get owls to mug for the camera. Even in captivity the birds remain aloof, unruffled by the flash and unmoved by attempts to bribe them. Photographer Brad Wilson learned that lesson firsthand after trying to win over owls from the World Bird Sanctuary in St. Louis and The Wildlife Center near Española, New Mexico. He spent hours with each bird, trying to capture its direct gaze. “It’s hard to get animals to look at you like humans do,” he says. “That shot became my holy grail.” It’s not easy to get owls to mug for the camera. Even in captivity the birds remain aloof, unruffled by the flash and unmoved by attempts to bribe them. Photographer Brad Wilson learned that lesson firsthand after trying to win over owls from the World Bird Sanctuary in St. Louis and The Wildlife Center near Española, New Mexico. He spent hours with each bird, trying to capture its direct gaze. “It’s hard to get animals to look at you like humans do,” he says. “That shot became my holy grail.” Wilson is an expert at point-blank portraits. His series “Affinity” features 65 species, including a white rhino, a white tiger, an Arctic fox, and an Egyptian Vulture. But owls were the most compelling and challenging subjects, he says. It takes years of building mutual trust before an owl will accept physical contact from a single person, says Wilson, and “owls don’t extend that privilege to other humans.” Read more Why David Allen Sibley, King of the Birders, Became the Pandemic’s Unlikeliest Celebrity  When droves of quarantined Americans took up bird-watching, they turned to guide books by a soft-spoken Western Mass. ornithologist, one of the best there’s ever been. When droves of quarantined Americans took up bird-watching, they turned to guide books by a soft-spoken Western Mass. ornithologist, one of the best there’s ever been.

The first thing I notice about David Allen Sibley, as we are standing in his driveway in Deerfield, is that he is quiet and shy. This only adds to the air of mystery I’d surrounded him in, and God knows I had spent the past couple years blanketing the man in plenty. That’s because Sibley — or, more accurately, the idea of “Sibley,” which has meant different things to different people these past two decades — had arrived in my life at the exact moment when I was beginning an internal debate. These simultaneous events — the existential crisis, and the first time I heard the word “Sibley” — occurred as I was standing in a parking lot near a trailhead in Bolton, just wrapping up an evening where I had been shadowing a group of expert birders who were competing in the Mass Audubon Bird-a-thon, an annual contest where teams of birders attempt to see or hear the most species in 24 hours. Read more Birding: Taking Proper Names Out of Bird Names is the Proper Thing to Do  It's a chance to not only simplify naming conventions, but also to address sexist and racist concerns from some people for which the birds were named. It's a chance to not only simplify naming conventions, but also to address sexist and racist concerns from some people for which the birds were named.

The American Ornithological Society has a committee of taxonomic experts who maintain the checklist of North American birds. Birding organizations, publishers of field guides and the birding community, in general, follow this checklist. The committee is responsible for evaluating records that will add new species to the checklist, considers evidence for splitting an existing species into two or more new species as well as evidence for combining existing species into a single species. The committee also maintains a list of standardized common names for North American birds. These standardized names are appreciated by most birders. It’s a lot easier to call the bird you saw a blue jay rather than Cyanocitta cristata. Read more | | THE ART OF BIRDS Almost A Year After Central Park Karen, The Brothers’ Network Continues to Showcase Black Birders and Artists  It’s been almost a year since Keith Russell, an ornithologist in Philadelphia, read about how Christian Cooper’s bird-watching trip in Central Park went awry. It’s been almost a year since Keith Russell, an ornithologist in Philadelphia, read about how Christian Cooper’s bird-watching trip in Central Park went awry.

It was a scene that, as someone who goes out bird watching often, is familiar to Russell. Amy Cooper, a white woman, had her dog off the leash in a part of Central Park where birds like to visit. Christian Cooper, who is Black, asked her to leash the dog as is required in the area. Tension between birders and dog owners is not unusual, said Russell, but Amy’s response was something he’d never experienced. She called the police, telling the dispatcher her life was being threatened — it wasn’t — and stressing the fact Christian was “African American,” feigning distress. Though the incident took place in Central Park, the fact that it occurred around the time George Floyd and other Black men were killed by police made Russell reconsider ever asking someone to leash their dog. Read more Meet Elizabeth Gould, the Gifted Artist Behind Her Husband's Famous

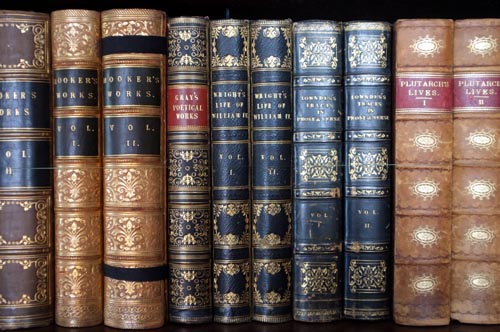

Bird Books  John Gould's ornithology books were hugely popular and cemented his name in history. But his wife's illustrations were a big reason why. John Gould's ornithology books were hugely popular and cemented his name in history. But his wife's illustrations were a big reason why.

In 1830, when English taxidermist John Gould was keen to publish his first volume of bird species, his wife Elizabeth asked him who would create the illustrations. She knew her unartistic husband wouldn’t be up to the task. According to an 1893 biography of John, he replied, “Why you, of course.” Within the next decade, Elizabeth’s artistic talent would help cement the Gould name in ornithological history. But unlike her husband, her name would be largely forgotten.

“We know that John Gould himself was not a particularly talented artist,” says Robert Peck, a curator and historian at Drexel University. John could produce outlines and rough sketches, but Elizabeth created the final illustrations that appeared in their collections. Born in England to a middle-class military family, Elizabeth likely studied drawing, painting, and botany, which was customary for young Victorian women. By the time she met John in her early twenties, she was working as a governess and he was a curator and taxidermist at the Zoological Society of London. In a surviving letter to her mother, Elizabeth wrote that she found the work dull and lonely. Elizabeth and John married in 1829, and the couple wasted no time in employing her artistic talents: A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains was published just two years later. Read more To Draw Nature, Pick Up a Pencil and Really Look  With a few basic tips you can begin to draw the creatures around you, and remember the joy they bring. With a few basic tips you can begin to draw the creatures around you, and remember the joy they bring.

If you enjoy watching birds floating by or chipmunks scampering across your lawn, why not have a go at drawing them to remember what gave you some cheer? With a few basic tips, you can begin making simple drawings. Don’t worry about how good they are. Enjoy that you are learning to see nature. As the writer and naturalist Rachel Carson said, “Those who notice nature will never be bored.”  All you need is a pencil and paper. If your desired subject is not right in front of you, or moves too quickly for you to capture, a field guide or a clear photo from a magazine or online search will do. Choose an image that is in profile, which makes it easier to see your subject’s shape. Keep your drawing small, no more than four inches to begin. All you need is a pencil and paper. If your desired subject is not right in front of you, or moves too quickly for you to capture, a field guide or a clear photo from a magazine or online search will do. Choose an image that is in profile, which makes it easier to see your subject’s shape. Keep your drawing small, no more than four inches to begin. How to begin: Find five or 10 minutes in your day to slow down and be with nature. What would you like to draw, to learn more about? It could be anything — a butterfly, a chickadee, an oak tree, even a green pepper or an apple. Look very carefully at your subject, figuring out its basic shape. How did it grow and where? How does it live? Remember, this is a stress reliever, not a stress creator. Getting to know your animal is the important thing. Try doing sketches of what you see directly, mostly looking at the animal and not at your paper. Read more Follow These Amazing Instagram Accounts for Beautiful Bird Photos  Need more feathers in your feed? These photographers have you covered. Need more feathers in your feed? These photographers have you covered.

Here at Audubon, we love ourselves a good bird photo. So, as we wait for the 2021 Audubon Photography Awards winners to be announced, we’ve been scouring Instagram for the very best #birdstagrams to tide us over. Read on to find our favorites, and hit that "Follow" button to add some fine feathered photography to your day. And don't forget to also follow Audubon's own Instagram account for even more birdy goodness. Georgia-based photographer Jason Collins posts gorgeous photos from his regular birding trips in and around Eastman, Georgia, as well as farther afield. Whether he’s in his own backyard or traveling internationally to Greece or Colombia, he’s on the lookout for birds to capture with his camera. Captions provide IDs and snippets of information about the bird in the shot. Read more | | | | ACTION/ADVOCACY Birds Are Telling Us We Must Act Now to Ensure Our Planet Can Sustain Wildlife and People  Why should anyone care about birds? Here are 5 key ways that birds help people—download a flier and/or share on social to help others. Why should anyone care about birds? Here are 5 key ways that birds help people—download a flier and/or share on social to help others.

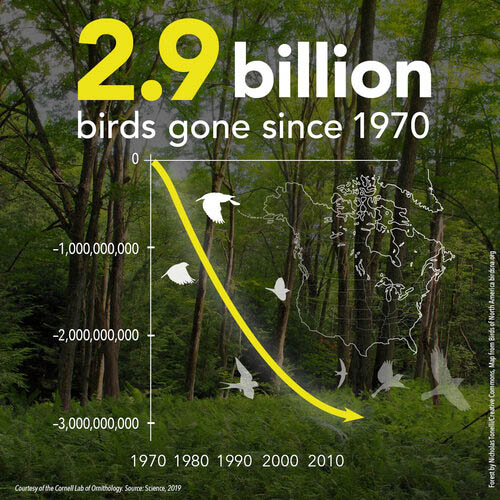

We’ve Lost One in Four Birds Since 1970

Across the continent, numbers have plummeted, even among common species In less than a single lifetime, North America has lost more than one in four of its birds, according to a report in the world’s leading scientific journal.  Published in Science by researchers at seven institutions, the findings show that 2.9 billion breeding adult birds have been lost since 1970, including birds in every ecosystem. Published in Science by researchers at seven institutions, the findings show that 2.9 billion breeding adult birds have been lost since 1970, including birds in every ecosystem.

The losses include iconic songsters such as Eastern and Western Meadowlarks (down by 139 million) and favorite birds at feeders, such as Dark-eyed Juncos (down by 168 million) and sweet-singing White-throated Sparrows (down by 93 million).

The disappearance of even common species indicates a general shift in our ecosystems’ ability to support basic birdlife, the scientists conclude. How Can You Help Make a Bird-Friendly Planet? Read more ‘Birds are a perfect way to get people interested in science’: Birding Game Developed by Coquitlam Teen Takes Flight  Coquitlam's Adam Dhalla has spent more than two years developing a birdwatching game he hopes will get other young people interested in the hobby and conserving birds' habitat. Coquitlam's Adam Dhalla has spent more than two years developing a birdwatching game he hopes will get other young people interested in the hobby and conserving birds' habitat.

A birding game developed by a Coquitlam teenager is taking flight.

Adam Dhalla, 16, says his Find My Birds mobile app is already being played in 45 countries on six continents since it was first made available on the Apple and Google app stores in April.  In the works for more than two years, the game is an animated virtual birding experience that drops users into various environments like Saguaro National Park in Arizona where they’ll able to walk around and view and photograph birds in their habitat of native flora. When a bird is spotted, it can be logged into a field guide that also provides information about the bird. The more times you find a bird species, the more information — like the birds’ diet, conservation efforts, audio recordings of its calls, photos and video — you get. In the works for more than two years, the game is an animated virtual birding experience that drops users into various environments like Saguaro National Park in Arizona where they’ll able to walk around and view and photograph birds in their habitat of native flora. When a bird is spotted, it can be logged into a field guide that also provides information about the bird. The more times you find a bird species, the more information — like the birds’ diet, conservation efforts, audio recordings of its calls, photos and video — you get. As the game progresses, users are also challenged with conservation quests to remove invasive species of plants or help rescue other endangered birds. Read more Biden Administration Reverses Trump Rollback of Migratory Bird Treaty Act  The Biden administration proposed a new rule that would reverse the Trump administration’s weakening of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The Act’s implementation was weakened in 2020, allowing industrial operations and individuals to unintentionally kill many birds without accountability. It is one of several wildlife protections rolled back by the former administration, and this action by President Biden signals a new commitment to America’s wildlife alongside his commitment to protect 30% of lands and waters by 2030. Two hundred seventy-nine bird species are now endangered in the Americas, and the extinction crisis is only accelerating. This damage to migratory bird populations harms ecosystems and Indigenous communities across continents that rely on these species. The Biden administration proposed a new rule that would reverse the Trump administration’s weakening of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The Act’s implementation was weakened in 2020, allowing industrial operations and individuals to unintentionally kill many birds without accountability. It is one of several wildlife protections rolled back by the former administration, and this action by President Biden signals a new commitment to America’s wildlife alongside his commitment to protect 30% of lands and waters by 2030. Two hundred seventy-nine bird species are now endangered in the Americas, and the extinction crisis is only accelerating. This damage to migratory bird populations harms ecosystems and Indigenous communities across continents that rely on these species. Why This Matters: The world is facing a biodiversity crisis, losing more species each year than ever before. America’s bird populations are struggling to cope with climate change, and each year, industry in the U.S. kills an estimated 450 million to 1.1 billion birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is one of the country’s oldest wildlife protections, dating back 102 years. President Biden’s commitment to science-backed, bedrock conservation laws will serve him well as the administration seeks to implement one of the most significant conservation projects in the last 50 years, the “America the Beautiful” Plan that charts a course to achieve the 30% protection pledge. Read more Philadelphia Has Dimmed its Skyline After a 'mass collision' Killed Thousands of Migrating Birds  Nearly twenty buildings in Philadelphia are dimming their lights this spring after thousands of birds perished in the city's largest mass collision in recent history. Nearly twenty buildings in Philadelphia are dimming their lights this spring after thousands of birds perished in the city's largest mass collision in recent history.

The voluntary measure has been coordinated by "Bird Safe Philly" and continues until May 30 with the purpose of sparing the lives of some of the 100 million birds passing over the City of Brotherly Love on their semiannual migrations. To some, it might seem more intuitive to leave the lights on to help birds steer clear of buildings, but Robert Peck, a senior fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, explains most migrating fowl navigate by light; the sun, the moon and the stars. Fog and rain, which are quite common in spring and autumn, force birds to fly at lower altitudes. When they see the bright city lights, they are often dazzled, disoriented and confused. "Suddenly they have all these lights coming at them from different directions. It's overwhelming," Peck said. "They get turned around and they will fly into buildings and walls." Read more Many Partners Aim to Protect Nevada Wetlands for Shorebirds  Analysis at Lahontan Valley Wetlands identifies bird species for habitat management. Analysis at Lahontan Valley Wetlands identifies bird species for habitat management.

Update (05/14/2021): The analysis of shorebird counts described below has now been published in Western Birds, a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The described pending transfer of Carson Lake and Pasture from the Bureau of Reclamation to the Nevada Department of Wildlife has now occurred. A recent grant is enabling continued development of a foundation for shorebird management planning in the Lahontan Valley. Long-billed Dowitchers—shorebirds about the size of robins—annually migrate from breeding areas in Alaska and eastern Siberia to wintering areas in the southern United States, Mexico, and the northern part of Latin America. Along the way, surveys indicate that up to 150,000 Long-billed Dowitchers stop annually in the Lahontan Valley Wetlands, some 70 miles east of Reno, Nevada. In fact, comprehensive surveys across the entire Intermountain West show that Lahontan Valley’s Dowitcher numbers are among the highest in the region. Read more | | | | | | CLIMATE/ECOLOGY Biden’s Climate Chops Face A Big Test On Old-Growth Forests  In the Cascade Mountain Range of west-central Oregon, near the small town of MacKenzie Bridge, is an area of Willamette National Forest that’s home to a patchwork of mature Douglas fir and western hemlock. The oldest are between 120 and 150 years, towering more than 100 feet. In the Cascade Mountain Range of west-central Oregon, near the small town of MacKenzie Bridge, is an area of Willamette National Forest that’s home to a patchwork of mature Douglas fir and western hemlock. The oldest are between 120 and 150 years, towering more than 100 feet.

Few mature forests remain in the continental United States after decades of intensive logging. And, like so many before them, these trees could soon be gone as the U.S. Forest Service moves ahead with a plan that would allow about 2,000 acres to be cut down in what’s known as the “Flat Country” project. The Biden administration is pushing an aggressive environmental agenda, pledging to both slash greenhouse gas emissions at least in half and to conserve 30% of America’s lands and waters by 2030. Those commitments include broad language about the need to “invest in forest protection and forest management” and to “fight climate change with the natural solutions that our forests, agricultural lands, and the ocean provide.” Read more 17-year Cicadas: Bird Buffet or Big Disturbance?  As the emergence of 17-year cicadas, commonly referred to as Brood X, approaches, animal keepers are gearing up to keep an extra close eye on their charges, especially those that eat insects, to make sure they don't over-indulge. As the emergence of 17-year cicadas, commonly referred to as Brood X, approaches, animal keepers are gearing up to keep an extra close eye on their charges, especially those that eat insects, to make sure they don't over-indulge.

But of course, zoo animals aren't the only ones that eat cicadas. Local songbirds, including chickadees, bluebirds and cardinals, will take advantage of their abundance too, something Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists are eager to study. "This is an awesome opportunity to see how birds respond to a cicada emergence that occurs once every 17 years," said ecologist Brian Evans. "We're looking at how bird songs might change in response to the volume of the cicada calls and how nest success might change thanks to all of this new food in the environment." For more than two decades, Smithsonian scientists have partnered with homeowners, students and residents to track nesting birds through the Neighborhood Nestwatch program. Every year, Nestwatch citizen scientists partner with Smithsonian scientists to track and observe birds nesting in backyards, school yards and local parks. Read more | | | | | |  | BOOKS That Most Enchanting Bird in the World WHY PEACOCKS?

An Unlikely Search for Meaning in the World’s Most Magnificent Bird

By Sean Flynn  Immanuel Kant wrote that only humans are capable of appreciating beauty — a claim refuted soundly by the existence of the peacock. Immanuel Kant wrote that only humans are capable of appreciating beauty — a claim refuted soundly by the existence of the peacock.

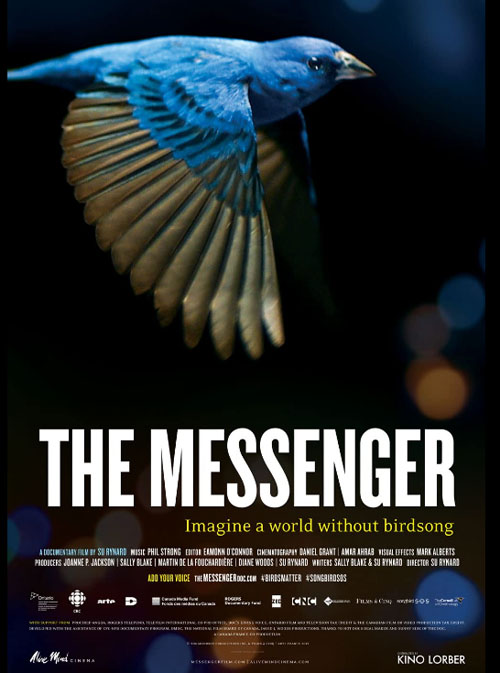

Before Charles Darwin, Westerners saw the peacock’s beauty as a gift from God to what we assumed was his favorite creation: people. But the peacock’s fabulous, extravagant tail was not crafted for our appreciation. As Darwin understood, and as subsequent science has proved, the intended audience for the peacock’s beauty is the lady peacock, or peahen, who is most apt to mate with the male whose tail she finds most enthralling. Still, it’s hard for a human to resist a peacock’s allure. When the journalist Sean Flynn saw one sitting on a farm roof, he was awe-struck. “His train hung over the gutter like a ristra, catching speckles of midday sunlight sneaking through the trees,” he writes. The feathers were “sparks of green and gold, copper and turquoise, burgundy and blue-black, all of them flashing and fading again with the slightest movement. … It was the most magnificent creature I had ever seen.” Soon afterward, and somewhat to his own surprise, Flynn takes three of these birds back to his North Carolina, to what he calls his “faux farm,” the next county over. His family names them Ethel, Carl and — a contribution from his younger son, Emmett — Mr. Pickle. The drama of their lives forms the story line of “Why Peacocks? An Unlikely Search for Meaning in the World’s Most Magnificent Bird.” Read more | |  The Messenger

Directed by Su Rynard  In ancient times humans looked to the flights and songs of birds to foretell the future. Today once again the birds have something to tell us. In ancient times humans looked to the flights and songs of birds to foretell the future. Today once again the birds have something to tell us.

Su Rynard’s wide-ranging and contemplative documentary THE MESSENGER explores our deep-seated connection to birds and warns that the uncertain fate of songbirds might mirror our own. Moving from the northern reaches of the Boreal Forest to the base of Mount Ararat in Turkey to the streets of New York, THE MESSENGER brings us face-to-face with a remarkable variety of human-made perils that have devastated thrushes, warblers, orioles, tanagers, grosbeaks and many other airborne music-makers.

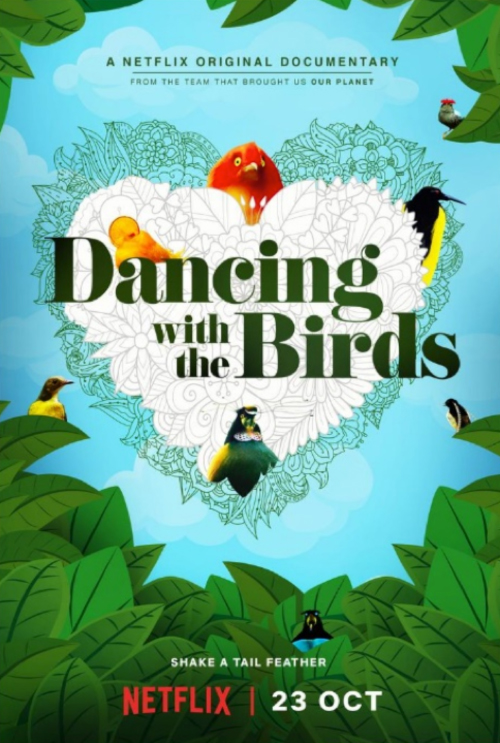

“The Messenger is an artful investigation into the causes of songbird mass depletion and the people working to turn the tide. This visually thrilling film reveals how the issues facing birds also pose daunting implications for our planet”. – IMDb On one level, THE MESSENGER is an engaging, visually stunning, emotional journey, one that mixes its elegiac message with hopeful notes and unique glances into the influence of songbirds on our own expressions of the soul. On another level, THE MESSENGER is the artful story about the mass depletion of songbirds on multiple continents, and about those who are working to turn the tide. Watch the trailer here Read more. RCC Recommends Dancing with the Birds, a Netflix Documentary  From the 9-step choreographed dance of the Carola's Parotia to the meter-tall twig, moss, and leaf structure of the Macgregor's bowerbird, the mating patterns of birds of paradise are complex and awe-inspiring. In the Netflix documentary Dancing with the Birds (2019), narrator Stephen Fry marvels alongside the audience at the wonders of birds of paradise. Covering 8 species and 5 categories of mating routines, the documentary grants the watcher a glance into hidden bird behaviors: mimicking the barking of a dog to be rid of a troublesome pig, scaring off rival males by waving a leaf to warn “this is my territory”, and, above all, dancing to win over a female’s heart. From the 9-step choreographed dance of the Carola's Parotia to the meter-tall twig, moss, and leaf structure of the Macgregor's bowerbird, the mating patterns of birds of paradise are complex and awe-inspiring. In the Netflix documentary Dancing with the Birds (2019), narrator Stephen Fry marvels alongside the audience at the wonders of birds of paradise. Covering 8 species and 5 categories of mating routines, the documentary grants the watcher a glance into hidden bird behaviors: mimicking the barking of a dog to be rid of a troublesome pig, scaring off rival males by waving a leaf to warn “this is my territory”, and, above all, dancing to win over a female’s heart.

Directed and written by Huw Cordey, Dancing with the Birds inspires smiles, chuckles, and wide-eyes in its audience. This 50-minute documentary provides the chance to learn about the unique species that inhabit the Earth while also reminding us of the times we’ve watched in wonder at the singing, hopping, swooping birds in our own backyards. With narration that illustrates the quirks of each individual bird and a soundtrack brimming with jazz, disco, and swing music, Dancing with the Birds is a joyful reminder of the life that surrounds us. This documentary received a 95% on Rotten Tomatoes. Watch the trailer here. Reviewer Isabel Wood, an RCC Presidential Fellow from Duke University, and the RCC’s new Bird Watch and Wonder editor (with Bob Musil and Ross Feldner), thinks Dancing with the Birds is fascinating bird watching at home, or in the classroom. | | | | | |  The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. | | | |  Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. | | | | | | | | | | | |