| | |  This month, the news overflowed with stories about birds! The Great Backyard Bird Count, a grassroots science event that uses eBird to compile data on birds around the world, occurred between February 18th and the 21st. Stories about the successes of this count were shared around the country, from Chicago to Monterey County, and around the world, from Canada to India. In fact, you can see how expansive this bird count is in real-time here. These community-run bird counting events allow scientists to conduct important research on bird populations and on how to best conserve these beloved species. This month, the news overflowed with stories about birds! The Great Backyard Bird Count, a grassroots science event that uses eBird to compile data on birds around the world, occurred between February 18th and the 21st. Stories about the successes of this count were shared around the country, from Chicago to Monterey County, and around the world, from Canada to India. In fact, you can see how expansive this bird count is in real-time here. These community-run bird counting events allow scientists to conduct important research on bird populations and on how to best conserve these beloved species.

February has proven to be a month packed with data collection through birding, but what about the results of some of these data collection movements? This month, many biological and ecological effects of climate change on birds and their habitats were published and caused a stir. For example, birds are shrinking, ending up in unlikely places, and even (surprisingly) getting divorced. Your birding helps scientists publish these findings and sheds light on the problems bird species around the country and world are facing. February has proven to be a month packed with data collection through birding, but what about the results of some of these data collection movements? This month, many biological and ecological effects of climate change on birds and their habitats were published and caused a stir. For example, birds are shrinking, ending up in unlikely places, and even (surprisingly) getting divorced. Your birding helps scientists publish these findings and sheds light on the problems bird species around the country and world are facing.

For more bird news, books, games (a new addition to our newsletter), and events, continue reading the February issue of RCC’s Bird Watch and Wonder. | | | | | | | | Virtual Attwater’s Prairie Chicken Festival  March 26 @ 7:00 am - March 27 @ 8:00 am CDT • Virtual March 26 @ 7:00 am - March 27 @ 8:00 am CDT • Virtual

Come see the endangered Attwater’s prairie-chickens dance in their native habitat.

At this time, the viewings are planned virtually (as in 2021) on our Facebook page from 7 am to 8 am. Check back at our website to see if early morning van tours will be available in 2022 to take participants up to one of the booming grounds to watch the male prairie-chicken’s famous courtship dance. If held in person, the weekend will include native plant guided tours, bird walks with experienced birders, Native American dance presentations, refuge van tours, and a merchandise booth sponsored by the Friends of Attwater Prairie Chicken Refuge. Contact: Attwater Prairie Chicken NWR • 979-234-3021 Read more | | | | | | | | | | | | Birds Are Remarkable and Beautiful Animals – and They’re Disappearing From Our World In the past half century, North America has lost a fourth of its birds. Earth is now a coal mine, and every wild bird is a canary. When the poet Mary Oliver wrote “Instructions for living a life,” she reminded us: “Pay attention. Be astounded. Tell about it.” This past autumn, wildlife officials announced that a bird, a male bar-tailed godwit, flew nonstop across the Pacific Ocean 8,100 miles from Alaska to Australia in just under 10 days. Fitted with a small solar-powered satellite tag, the godwit achieved “a land bird flight record”. | | | | | | Weekly Data: How Many Firds Are Really Killed By Wind Turbines? The rapid spread of wind power will see millions of birds killed each year, but this still pales in comparison with deaths from other hazards. Ever since the first commercial wind turbines came online in the 1980s, there have been people preoccupied by their negative impacts on the environment. Whether it be criticisms of turbines as blights on the landscape, scepticism at the complicated mineral requirements of the technology, or anger at noise produced by the blades as they turn, the anti-wind lobby has been fierce. | | | | | | Sea-eagle “Invisibility” Shows Why Study of Bird Movements is Not Easy The Steller’s sea-eagle has disappeared. At the time of this writing, the bird had not been reported since January 24, when it was back in Boothbay Harbor and on Southport Island after a few days over at Pemaquid Harbor. Of course, many people are still searching for it on a daily basis. But how far from the last place it was sighted should they search? This bird is clearly very unpredictable given it’s half a world away from where its fellow sea-eagles are at the moment, so it’s probably presumptuous for anyone to guess what it might be doing. | | | | | | | | New York’s Heritage Wind Decision Aims to Reduce Project’s Impact on Birds The state’s new Office of Renewable Energy Siting sets a precedent acknowledging the need to minimize environmental impacts. Members of the conservation community, including American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Genesee Valley Audubon Society, and Rochester Birding Association, have long expressed grave concerns about the Heritage Wind project. While some of these concerns remain, ABC believes that ORES rendered a thoughtful decision that reasonably balances renewable energy development with the need to protect the state's declining bird populations. | | | | | | | | Annual Bird Count Helps Develop Science, Conservation Policies in South Carolina On an unseasonably warm December day, a group of passionate birders gathered to take part in an annual tradition that is a bit different from typical holiday customs. Armed with binoculars and tally sheets, they set out to shape the future. This tradition, known as the Christmas Bird Count, represents one of the largest community science projects in the Western Hemisphere. The data collected is vital to informing science policy and conservation efforts here in South Carolina and beyond. | | | | | | Indigenous-led Conservation in Hudson and James Bays In late August, while most of us are soaking up the last days of summer, migratory breeding birds of the Arctic and the Boreal Forest within Canada are mobilizing to return to southern wintering grounds. For many of the shorebirds, waterbirds, and waterfowl that breed in the far north, this journey will include stops along the shorelines of Hudson and James Bays. Extensive coastal marshes, wide tidal flats, and eelgrass beds make it one of the most important stopover and staging areas for migratory birds in North America. | | | | | | | | Many Birds Are Shrinking and Growing Longer Wings as the World Warms. Why? A growing body of research suggests a warming world could mean smaller birds with longer wings, but nothing about the findings is settled. Climate change is massively altering our world. Hotter temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, rising sea levels, more frequent wildfires, and melting sea ice are all affecting birds and their habitats. But climate change may be having another, less intuitive impact on birds: A host of scientific studies show that birds are gradually shape-shifting—their bodies are miniaturizing at the same time as their wings grow longer. | | | | | | | | | | An Arctic Bird Ended Up in Acton. Is Climate Change to Blame? Last month’s Winter Storm Izzy brought chaos to Massachusetts, downing power lines and tree branches, spurring coastal flooding, and leaving thousands in the dark due to power outages. The storm may have been the most disorienting, however, for one small creature: an emaciated Arctic bird found by an Acton couple. The bird was later identified as a thick-billed murre, a species that spends that spends summers nesting in the rocky coasts of the High Arctic and winters in Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and northern Europe. Needless to say, Acton is way out of its normal range. | | | | | | Polar Bear Inbreeding and Bird 'divorces': Weird Ways Climate Change is Affecting Animal Species Species are adapting to warmer global temperatures, some in unusual ways. The world's biodiversity is constantly being threatened by warming temperatures and extreme changes in climate and weather patterns. And while that "doom and gloom" is the typical discourse surrounding how climate change is affecting biodiversity, another interesting aspect of the warming temperatures is how different species have been adapting over the decades, as the warming progresses, experts say. | | | | | | | | Birds Shuffle and Repeat Their Tunes to Keep the Audience Listening The tweets of a little song sparrow and its "bird brain" are a lot more complex and akin to human language than anyone realized. A new study finds that male sparrows deliberately shuffle and mix their song repertoire possibly as a way to keep it interesting for their female audience. The research, from the lab of Stephen Nowicki, Duke University professor of biology and member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, and colleagues at the University of Miami, shows that singing males keep track of the order of their songs and how often each one is sung for up to 30 minutes so they can curate both their current playlist and the next one. | | | | | | Red Knots, Northern Gannets Highlight Christmas Bird Count The hunt was on for all kinds of birds on Ocracoke as dozens of avid birders fanned out on the island in late December for the annual Christmas Bird Count. A red-breasted nuthatch was what Jeffrey Beane, Stephanie Horton and Lloyd Lewis were trying to find early in the morning as they strolled the village. “It’s usually found in Hammock Hills,” said Beane, who is the collections manager for herpetology with North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh. | | | | | | Answering an Age-Old Mystery: How Do Birds Actually Fly? Have you ever looked up to see a hawk soar overhead, or a small chickadee flit by and wondered: How do they do that? Believe it or not, scientists never really knew either—until now. Talia Lowi-Merri: I looked at the relationship between form and function in the most basic sense. Talia Lowi-Merri is a Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto in Canada. She says bird flight has everything to do with the shape and size of a bird’s sternum, or breastbone. Bird sternums have a projection from the middle called the keel, and this is where the flight muscles are attached. | | | | | | 10 of the Biggest Birds on Earth Discover what life is like for some of the biggest birds to roam the planet Some of the biggest birds on Earth can stand taller than any NBA player and spread their wings wider than kings size bed. There are almost 10,000 species of birds on Earth and they come in all different shapes and sizes — from the tiny bee hummingbird to the massive ostrich. Here are 10 of the biggest birds to inhabit our planet, including the tallest, heaviest and those whose wings spread the furthest. | | | | | | | | If Rover Can Make It Here, Perhaps Bald Eagles Can Make It Anywhere A white-headed raptor has been preying on smaller birds in Central Park. It’s come a long way since conservationists affixed aluminum bands to its legs four years ago. Visitors to Central Park’s reservoir in New York are taking in a drama filled with feathers. Its star performer, thrilling parkgoers and terrorizing gulls, is Rover, a bald eagle. The city’s birders have been tracking Rover for two years, and some point to his ongoing story as demonstrating the conservation benefits of attaching aluminum bands to the legs of threatened bird species when they are young. | | | | | | A Bird in the Hand | Chesapeake Bay Magazine The little song sparrow doesn’t know it, but it may become a bellwether for its species. Feet up, head gently cradled between Jim Gruber’s index and middle fingers, it fusses as the bespectacled researcher crimps a tiny aluminum anklet around one of its legs. Further avian indignity ensues. The bird’s wing is measured. Its estimated age and its gender are noted. Gruber blows softly on its breast and belly feathers to assess its fat content. Finally, he weighs the sparrow by carefully inserting it headfirst into a long plastic cone attached to a digital scale. | | | | | | Birds of Ocracoke: The Blue Jay It can be surprising that some bird species, which are common and easily seen on the mainland of North Carolina, can be few in number or nonexistent on Ocracoke Island. On the other hand, we have some common birds that are the envy of many. We get to see Brown Pelicans, White Ibis and Royal Terns flying overhead much of the year and Great-crested Flycatchers nesting in our village. The Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) is present year round in the village, but not regularly seen or heard. Seasonally, they are higher in numbers in summer. | | | | | | | | These Delightful Photos Highlight How Native Plants Support Birds Capturing a crisp image of a bird in flight, two mates lovingly preening each other, or an intense predator-prey interaction are coveted shots for any photographer. However, photographing birds with native plants—not just any plant—offers an exciting and captivating challenge. Launched in 2019, the Plants for Birds category of the Audubon Photography Awards aims to put just as much emphasis on the flora as the fauna in each shot—and the entries have only gotten better each year. | | | | | | | |  | | | |  Author reluctantly embraces birding as a hobby. Author reluctantly embraces birding as a hobby.

I almost never read books twice. "Field Notes from an Unintentional Birder" is an exception, even with a title I found off-putting.

I read it happily, and while reading it again will honestly say it is the best-written bird book I've come across.

The author, Julia Zarankin, tells a great story, and has a great story to tell. The book is as much about her as birds. It more or less begins the moment she realizes that when her newborn nephew is her age she will be 82.

She has a marriage soon to end, a career that no longer fits, and a nagging question: Is this all there is?

She is looking for a hobby. She and her sister meet a birding couple, they talk, the birders non-stoppable about what they have seen and heard. Eventually, the birding woman says, "If you're very very quiet you might hear a bird." Our heroine, however, is bored. Some months later, talking to her sister, she admits she has not found a hobby that fits. "What are you looking for?" "Something that will exercise my patience." Read more | | | | | | |  Stotts' new memoir details his unlikely journey to the ancient art. Now, his dream is to inspire more people like him to discover a love for raptors. Stotts' new memoir details his unlikely journey to the ancient art. Now, his dream is to inspire more people like him to discover a love for raptors.

Rodney Stotts is a master falconer who has spent nearly a decade training and apprenticing to trap, care for, and teach raptors to hunt alongside humans. (His bird of choice? Harris’s Hawks.) But Stotts has spent just as much of his career educating others—and helping more people realize that falconry is something they can do, too.

In his new memoir, Bird Brother: A Falconer’s Journey and the Healing Power of Wildlife, Stotts shares how he arrived at that revelation. With humor and a deep respect for those who influenced him, Stotts recounts how an innate love of nature stuck with him through years of ups and downs. He grew up in housing projects in southeast Washington, D.C., and in the early 1990s took a job cleaning up the Anacostia River with the Earth Conservation Corps (ECC), which set him on a path of becoming a conservationist. All the while, however, he juggled various other part-time jobs, including dealing drugs. In 2002, he was sent to jail due to more punishing laws about possession of marijuana, but by then he’d already started helping with raptor rehabilitation at the ECC. When he was released in 2003, he had a sense of clarity about what he wanted to do with his life. Ever since, he’s dedicated his time to falconry, educating people about raptors, and eventually training his son Mike to be a falconer, too. Read more | | | | | | | | |  Wingspan is ultimately about biodiversity, but I can’t help but see it fitting into a broader cultural reckoning. Wingspan is ultimately about biodiversity, but I can’t help but see it fitting into a broader cultural reckoning.

There I was — down to my last turn, sitting on a cache of rodents, and holding the pair of eggs needed to activate a bird of prey that I’d been hoping to slot into my forest habitat. “I will play my great horned owl, and I’ll pay for it with my army of rats,” I announced. Proudly, I drew the owl and set it on its spot on the board.

Lex, my partner, laughed. “Okay, weirdo,” she said, grabbing a pencil and scorecard. I’ve always struggled with board games. If the gameplay is even remotely involved, I’ll quickly lose interest. Headier “hobby” titles like Settlers of Catan, or even a mass-audience legacy game like Monopoly, require levels of time and commitment that I find overwhelming, and I’ve seen how they can feed stressed-out competitive tendencies and otherwise kill a vibe. I’d rather listen to a record. But I’ve found myself delighted by Wingspan, the hit board game that has turned a multimillion-dollar industry on its head since its release in 2019. We’d been hearing about it from birding-adjacent friends for a minute and decided, during the recent peak of the omicron wave, to drop the $60 for the indie breakout from Missouri-based Stonemaier Games. Now I’m wondering what took us so long. Read more | | | | | | |  The daily word quiz that has taken the internet by storm now has a version for birders. Just make sure you know your banding codes. The daily word quiz that has taken the internet by storm now has a version for birders. Just make sure you know your banding codes.

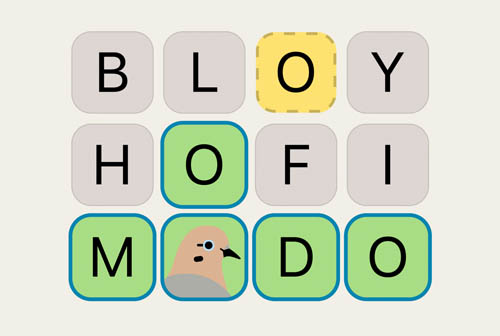

If you've spent more than five minutes online this month, you've likely either played Wordle or seen people sharing the results of their games. At this moment, that 6x5 grid of tiles seems virtually inescapable.

For those who have somehow entirely avoided the game up to this point, here's the gist: Wordle is a word-guessing puzzle that gives you six tries to guess a five-letter mystery word using the process of elimination. Correct letters placed in the correct tiles are marked green, and correct letters in the wrong tiles are yellow. Completely wrong letters are grayed out. On each attempt, reshuffle and replace accordingly. Sounds simple, right? It can be—and yet, it can also be surpringly difficult! Either way, Wordle is a whole heap of fun, and each day a new word provides a fresh challenge. You can learn more about Wordle's creator and the game's backstory here. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Wordle and its popularity have already inspired a slew of spinoffs. In fact, there's now one for the four-letter banding codes, or alpha codes, researchers use as shorthand for species' names—and it just so happened to be designed by Audubon's very own graphic designer Alex Tomlinson. Launched this week, BRDL has received rave reviews on Audubon Slack and Bird Twitter, so try your hand below to see if you can deduce which banding code is the mystery code of the day. If you're like most people and don't know your banding codes by heart, here's a full list. You can also find a quick tutorial on how they work below. Read more | | | | | |  Isabel Wood: RCC Presidential Fellow Isabel Wood: RCC Presidential Fellow

Isabel Wood is the co-lead with Ross Feldner and Bob Musil of the RCC Bird Watch and Wonder Program and works with Mackay Pierce on communications and social media.

She is a senior at Duke University majoring in Environmental Science and Policy with a certificate in Documentary Studies. isabel.wood@duke.edu | | | | | |  The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. | | | |  Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. | | | | | | | | | | | |