| | | Fall is the season of migration – crisp air, confusing warblers, the gr-ronk of geese, shorebirds starting sensationally long journeys. But Emily Anthes reports that migrating birds are in decline and face increasing obstacles. But for birders, our disrupted seasons, wildfires and smoke, hurricanes, flooding, and other effects of global climate change offer some delights, even as we worry and work to save the planet.   One of my favorites is the increasing sightings of wandering flocks of flamingos which are rarely seen in the U.S., even in Florida. Now they have been spotted all along the East Coast, including North Carolina from where I have just returned. And my native New York City, long a rich visiting spot for birds and people, has growing numbers of unusual and rare species these days. How about a Brown Booby at Coney Island? Or Brown Pelicans on Long Island? One of my favorites is the increasing sightings of wandering flocks of flamingos which are rarely seen in the U.S., even in Florida. Now they have been spotted all along the East Coast, including North Carolina from where I have just returned. And my native New York City, long a rich visiting spot for birds and people, has growing numbers of unusual and rare species these days. How about a Brown Booby at Coney Island? Or Brown Pelicans on Long Island? Migration has affected us humans, too. Christian Cooper, the now renowned Black birder from Manhattan, knows that well. A White woman called 911 to report a man threatening her in Central Park’s Ramble, prime migrating bird territory, when Cooper, armed with binoculars and a bike helmet, was tracking a Mourning Warbler, saw that the woman was illegally with an unleashed dog (chasing it wildly) in a protected area. He asked her to leash her dog and leave. She refused. The rest of the story is history and leads to Cooper’s finding himself and fame as he birds across continents. He recounts his coming to terms with being Black and gay in the United States in his compelling and often humorous book, Better Living Through Birding, which I review in our “Books” section. That birds intersect with climate change, varied ecosystems, and diverse economic and social settings in the U.S., including those at the center of the Great Migration of Black Americans to the Midwest and North to escape the worst of racial violence and seek greater opportunity, is at the heart of a beautifully wrought, observant and reflective essay by Natalie Rose Richardson. In “Look Closely, or You’ll Miss It,” Richardson retraces her family’s migration from South Carolina to Chicago and begins to notice the connection between her family’s journey and the world, including birds, that surrounds her.  If we do look closely, there are encouraging signs for birds and birders. For instance, Currituck Sound, which stretches north from Kitty Hawk to Virginia Beach, was once a major flyway for migrating birds, but the slaughter of wading birds for plumage to adorn women’s hats and increasing pollution finally left a dying habitat. Now citizens and scientists are working to restore the sound to its former glories. The birds and Currituck Sound are making a comeback. If we do look closely, there are encouraging signs for birds and birders. For instance, Currituck Sound, which stretches north from Kitty Hawk to Virginia Beach, was once a major flyway for migrating birds, but the slaughter of wading birds for plumage to adorn women’s hats and increasing pollution finally left a dying habitat. Now citizens and scientists are working to restore the sound to its former glories. The birds and Currituck Sound are making a comeback.

That’s why birders and citizen scientists can still celebrate The Big Day, October 14. You’ll find all about it and how to participate in our “Events” section. It’s also why RCC’s bird maestro, Ross Feldner, is able to offer up one of his typically wondrous essays in “Bird Lore” on the amusing and astounding variety of birds and bird names in “Name That Flock! (“What the Flock?!?”)” And, as you observe and reflect on the world around you, be sure to check out this month’s “Best of Bird of the Week” and “Best of Momentary Meditations” before you migrate out for fall migration. With all its contradictions and wonders -- it is worth our working to preserve. | | | | | | | |  Bob Musil is the President & CEO of the Rachel Carson Council and author of Rachel Carson and Her Sisters: Extraordinary Women Who Have Shaped America’s Environment (Rutgers, 2016) and Washington in Spring: A Nature Journal for a Changing Capital (Bartleby, 2016). He is also the editor of the forthcoming annotated edition from Rutgers University Press of Rachel Carson’s Under the Sea-Wind with his Introduction, updated marine science, and historic and contemporary illustrations and photographs. Bob Musil is the President & CEO of the Rachel Carson Council and author of Rachel Carson and Her Sisters: Extraordinary Women Who Have Shaped America’s Environment (Rutgers, 2016) and Washington in Spring: A Nature Journal for a Changing Capital (Bartleby, 2016). He is also the editor of the forthcoming annotated edition from Rutgers University Press of Rachel Carson’s Under the Sea-Wind with his Introduction, updated marine science, and historic and contemporary illustrations and photographs. | | | | | | For Migrating Birds, It’s the Flight of Their Lives America’s birds are in trouble. Since 1970, nearly 3 billion birds have vanished from the skies over North America. Most of those losses have been in migratory species, which may breed in the United States or Canada in the summer before heading elsewhere for the winter. Many spend more time living on Caribbean beaches or in Costa Rican forests than they do in American backyards. “They’re really visitors to North America,” said Viviana Ruiz-Gutierrez, co-director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. | | | | | | | | Name That Flock! (“What the Flock?!?”) Flock names can be descriptive either of a group of birds or their behavior and personalities. A flock of crows, as most of us know, is called a “murder” which relates to superstitions about crows being a harbinger of death. But what about these, a radiance, a whirl, a parliament? Why do birds flock, anyway? Birds flock for two main reasons: food and protection. When in a flock, it is easier for birds to detect danger since each bird can be looking in a different direction. | | | | | | | | In Defense of Pigeons Pigeons simply don’t deserve the bad press they get. If you ask people why they like their favourite animal, they will tell you about the incredible things the creature can do, its relatable characteristics or its interesting looks. Few would be likely to cite the pigeon as theirs. Many people think of them as vermin rather than wildlife. People’s utter disdain for feral pigeons breaks my heart. Sit in a park at lunchtime, anywhere in the world, and you’re almost certain to witness people lashing out at pigeons. | | | | | | | | Look Closely, or You’ll Miss It Sherry Williams—opening the door with an assaulting smile and waving away my apology with her hands—does not seem to care that I am late. I’ve come to meet her at her workplace, the Bronzeville Historical Society, located in a nondescript two-story brick building on the corner of 45th and King Drive on Chicago’s South Side. Google Maps sent me to the old address—ten blocks north—and the only indication of the new office on 45th Street is an 8 1/2-by-11-inch printer-paper sign taped to a door on the bare building’s south face. | | | | | | | | In New York City, the Odds of Spotting a Rare Bird are Rising Sharp-eyed birders might spot brown boobies, a tropical species once rare even in the Southern states. A flock of Canada geese might just include a pink-footed goose, too. Birds that were once rare in New York City have been making more frequent appearances in recent years, to the thrill of local bird-watchers. But that excitement is tempered by the knowledge of what may be causing these changes: warming ocean temperatures, melting snowpacks and wildfires. | | | | | | | | | | Petrels ‘little superheroes’ to Researcher Kate Sutherland Researcher and island resident Kate Sutherland’s work studying the chemical isotopes of the feathers from black-capped petrels may lead to better understanding of the foraging habits — if not the varied physical appearance — of this difficult-to-study, endangered Gulf Stream bird species. Sutherland is set to present her findings in October at a joint Waterbird Society and Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative conference in Florida. | | | | | | | | Storm-blown Flamingos Show Up in North Carolina and Beyond Eleven of the leggy, pink waders were spotted on the Outer Banks. Jeff Lewis woke up Saturday morning with flamingos on his mind. The iconic pink wading birds would be an exceedingly rare sighting on the Outer Banks, where Jeff lives and has been birding for 35 years. But reports had been trickling in that Hurricane Idalia had blown small flocks of flamingos into Florida. Then on Friday, sightings popped up in Virginia and, of all places, Ohio. Maybe North Carolina could be next? | | | | | |  | | | The Trouble With Oil and Gas Infrastructure A new study led by the Wildlife Conservation Society that analyzed 17 years of migratory bird-nesting data in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, revealed that nest survival decreased significantly near high-use oil and gas infrastructure and its related noise, dust, traffic, air pollution, and other disturbances. Prudhoe Bay is the site of intensive energy development and is located on the Arctic Coastal Plain, one of the most important avian breeding grounds in the world. | | | | | | | | As Project Puffin Completes a Milestone Summer, Uncertainties Remain Because of the Effects of Climate Change. The 50th anniversary of Project Puffin has just ended, with researchers fully realizing how their quest has morphed from saving one bird to playing a part in saving the planet. Its purpose in 1973 was simply to return puffins to islands off the coast of Maine, where hunters had killed them off by the late 1800s. | | | | | | | | Warmer Oceans Are Driving More Frequent Seabird Die-Offs, Preventing Populations From Recovering It wasn’t the seabird carcasses that were unusual. Birds that die at sea frequently wash ashore. On regular surveys to tally bodies from Alaska to Central California, for example, volunteer data collectors might find 50 dead birds a day during normal peak periods at some beaches, such as after breeding season when lost fledglings appear or during migration when birds succumb to exhaustion. | | | | | | | | October Big Day—14 Oct 2023 Mark your calendars for October Big Day—14 Oct 2023! Like Global Big Day, October Big Day is an opportunity to unite around our shared love of birds. Last October, nearly 35,000 people from 185 countries submitted 80,000 checklists with eBird, demonstrating the power of birds to bring people together. Wherever you are on 14 October, take a few minutes to join in this global celebration. Participate from anywhere—even from home! By taking part in October Big Day you’re also celebrating Global Bird Weekend and World Migratory Bird Day. | | | | | | | | Pilot Projects May Prove vital in Currituck Sound Restoration Stretching north from the Wright Memorial Bridge at Kitty Hawk to the Back Bay of Virginia Beach, Currituck Sound was, at one time, the crown jewel of the Atlantic Flyway. A large, freshwater estuary teeming with subaquatic vegetation and dotted with innumerable low-lying islands and marsh habitat for ducks, geese and swans, migratory waterfowl by the hundreds of thousands flocked to its waters every fall and winter. | | | | | | | | Roseate Spoonbill It’s easy to see how this bird got its name with its rosy coloring and a spoon shaped bill. Modern field guide author Kenn Kaufman once said: “Roseate Spoonbills are gorgeous at a distance and bizarre up close.” This unique bird has striking pink plumage that became so popular on women’s hats in the 1800s that hunters almost drove them into extinction. They were able to recolonize in the early 1900s and slowly increased in number. Modern threats are mostly habitat loss. | | | | | | | | Measured Steps This Snowy Egret (small white heron) separated from a frenzied flock to walk with measured steps where the sea touched the rocky shore. The beauty of its white body drew me into the intensity of the waiting moments before it quickly struck its black beak through the water. Reflecting on this scene, I remind myself of the defining power of waiting moments. | | | | | | | | Musil Book Review Essay: Open Your Eyes and See Christian Cooper, Better Living Through Birding:

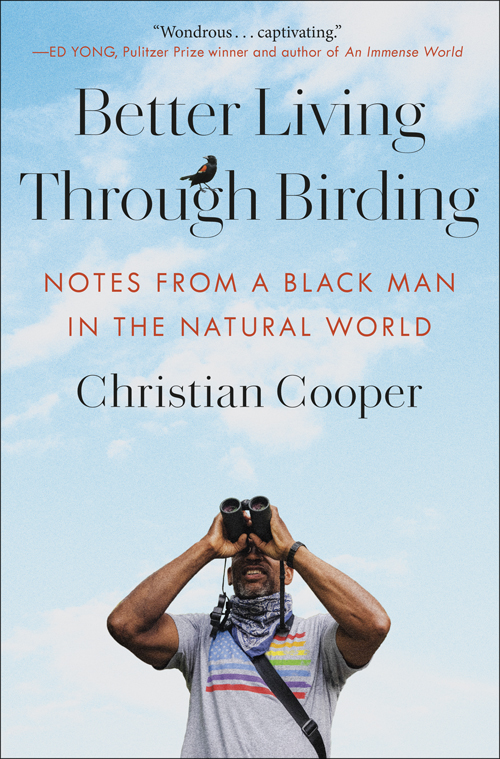

Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World (Random House, 2023)  I grew up just a few miles away from the noted birder, Christian Cooper. We must have roamed the same dunes, watched the same sanderlings scurrying through the surf, seen the same shells and sand sharks at Jones Beach. We developed a love of nature and birds from our parents on Long Island (his father, my mother). We love the same birds and even the sound of their names (Blackburnian Warbler). But we might as well have grown up on opposite sides of the planet. I am white, straight, and went to Yale. Cooper went to Harvard and is Black and queer. I grew up just a few miles away from the noted birder, Christian Cooper. We must have roamed the same dunes, watched the same sanderlings scurrying through the surf, seen the same shells and sand sharks at Jones Beach. We developed a love of nature and birds from our parents on Long Island (his father, my mother). We love the same birds and even the sound of their names (Blackburnian Warbler). But we might as well have grown up on opposite sides of the planet. I am white, straight, and went to Yale. Cooper went to Harvard and is Black and queer.

I opened his book expecting to travel along with Cooper on birding forays and, ultimately, to hear his own account of having a White woman in Central Park who refused his request to leash her dog call the police on him. She reported she was being threatened by a Black man with binoculars and a bike helmet.  Better Living Through Birding is indeed filled with wonderful birds and birding. It opens with an exhilarating account of his tracking the extremely rare Kirtland’s Warbler in Central Park. Cooper gets a text at his office that this rarity may be there and he dashes out so rapidly that his co-workers think someone must have died. The excitement in Central Park foreshadows Cooper’s later confrontation with Amy Cooper (no relation) and her dog, Henry, as he rushed to find the last warbler of the season, the ground hugging Mourning Warbler. Its habitat is exactly where Henry was bounding around with Amy shouting after him. But Cooper’s autobiographical odyssey offers far more than warbler observations, ospreys or owls. Better Living Through Birding is indeed filled with wonderful birds and birding. It opens with an exhilarating account of his tracking the extremely rare Kirtland’s Warbler in Central Park. Cooper gets a text at his office that this rarity may be there and he dashes out so rapidly that his co-workers think someone must have died. The excitement in Central Park foreshadows Cooper’s later confrontation with Amy Cooper (no relation) and her dog, Henry, as he rushed to find the last warbler of the season, the ground hugging Mourning Warbler. Its habitat is exactly where Henry was bounding around with Amy shouting after him. But Cooper’s autobiographical odyssey offers far more than warbler observations, ospreys or owls.

I grew up just a few miles away from the noted birder, Christian Cooper. We must have roamed the same dunes, watched the same sanderlings scurrying through the surf, seen the same shells and sand sharks at Jones Beach. We developed a love of nature and birds from our parents on Long Island (his father, my mother). We love the same birds and even the sound of their names (Blackburnian Warbler). But we might as well have grown up on opposite sides of the planet. I am white, straight, and went to Yale. Cooper went to Harvard and is Black and queer. I opened his book expecting to travel along with Cooper on birding forays and, ultimately, to hear his own account of having a White woman in Central Park who refused his request to leash her dog call the police on him. She reported she was being threatened by a Black man with binoculars and a bike helmet. Better Living Through Birding is indeed filled with wonderful birds and birding. It opens with an exhilarating account of his tracking the extremely rare Kirtland’s Warbler in Central Park. Cooper gets a text at his office that this rarity may be there and he dashes out so rapidly that his co-workers think someone must have died. The excitement in Central Park foreshadows Cooper’s later confrontation with Amy Cooper (no relation) and her dog, Henry, as he rushed to find the last warbler of the season, the ground hugging Mourning Warbler. Its habitat is exactly where Henry was bounding around with Amy shouting after him. But Cooper’s autobiographical odyssey offers far more than warbler observations, ospreys or owls.  | | | | | | The Sepetember 2023 issue of Bird Watch and Wonder was produced by Ross Feldner. | | | | | |  The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. | | | |  Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. | | | | | | | | | | | |