| | | As autumn leaves show their colors and we prepare to set our clocks back an hour after the end of October, we may feel nostalgic for the wonders of fall: Halloween costumes, jumping into leaf piles, enjoying a warm, spiced latte, the excitement of a new school year for younger folks, and, of course, the gorgeous scenery. But this time of year doesn’t bring reprieve for those still in the throes of the Atlantic hurricane season, which doesn’t officially conclude until November 30th. In recent years, fierce storms have occurred through the season’s final eight weeks and 2022 shows no signs of stopping early. This issue of the RCC Observer shows the widespread effects and differing responses to Hurricane Ian along the East Coast and the need for dramatic change in how the United States prepares for and deals with such climate-fueled disasters. Typically, marginalized populations—including communities of color, disabled people, low-income communities, and those experiencing homelessness—are more susceptible to the worst effects of tropical storms and hurricanes. While natural disasters do not discriminate against the type of person in their path, the response to these catastrophes definitely does. According to the New York Times, research shows that FEMA, the government agency responsible for helping Americans recover from disasters, often aids white disaster victims more than victims of color facing comparable damage. Puerto Ricans are still dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Maria and were ill equipped to withstand the intense flooding and infrastructure damage wrought by Hurricane Ian. Many residents faced uncertainty over food, water, and shelter post Ian. This has happened time and time again and Puerto Ricans are left asking, what about us?  Now is the time to invest in proactive, rather than reactive solutions to natural disasters. For decades, engineers have advocated for the use of sea walls, levees, and raised homes for beachfront properties to mitigate the impact of climate disasters. These, however, are short-term and often very costly solutions. If Hurricane Ian has shown us anything, it’s that in the end such solutions did absolutely nothing. Fort Myers and Sanibel Island in Florida are home to some of the wealthiest residents in the state. Nevertheless, Hurricane Ian devastated these areas. An early assessment in Florida shows that Hurricane Ian will cost some $40 billion in damages. What we can learn from the Sanibel experience is that what was visionary in the past may not be sustainable in the future. Now is the time to invest in proactive, rather than reactive solutions to natural disasters. For decades, engineers have advocated for the use of sea walls, levees, and raised homes for beachfront properties to mitigate the impact of climate disasters. These, however, are short-term and often very costly solutions. If Hurricane Ian has shown us anything, it’s that in the end such solutions did absolutely nothing. Fort Myers and Sanibel Island in Florida are home to some of the wealthiest residents in the state. Nevertheless, Hurricane Ian devastated these areas. An early assessment in Florida shows that Hurricane Ian will cost some $40 billion in damages. What we can learn from the Sanibel experience is that what was visionary in the past may not be sustainable in the future. We are certainly at a turning point when it comes to mitigating climate change. A feasible solution is investing in our natural resources. A study conducted by the US Geological Survey (USGS) found that across the U.S., coral reefs have helped safeguard the homes of more than 18,000 people and avert $1.8 billion in flood damage each year. In California, similar studies are being conducted that prove that investing in restoration projects like reefs, oysters, seagrass beds, and mangroves are the solution to the looming threat of climate change. The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act allocates $370 billion to national climate and clean energy spending, a huge step in the right direction of halving our national emissions by 2030, as outlined in the United States’ Paris Agreement Nationally Determined Contributions. While the administration has yet to take a no-exceptions stance on oil and gas offshore drilling, a major contributor of greenhouse gasses, the country is headed in a climate-forward direction, not least because of the educational campaigns around and promotion of renewable energy from environmental organizations like the Rachel Carson Council and concerned individuals like you.  Elsewhere in our October issue, you can take action to protect seabirds like the Atlantic Puffin and find Bob Musil’s latest book review of A Voyage Across an Ancient Ocean by David Goodrich, his recommendation for the right holiday gift for those relatives like cranky ol’ Uncle George. They may not want to hear about climate change, but just might enjoy an engaging, often humorous travelogue of Goodrich’s 1200 mile solo bike ride across the tar sands oil fields of Canada and the Dakotas that were created by the ancient sea that once covered half of North America. Elsewhere in our October issue, you can take action to protect seabirds like the Atlantic Puffin and find Bob Musil’s latest book review of A Voyage Across an Ancient Ocean by David Goodrich, his recommendation for the right holiday gift for those relatives like cranky ol’ Uncle George. They may not want to hear about climate change, but just might enjoy an engaging, often humorous travelogue of Goodrich’s 1200 mile solo bike ride across the tar sands oil fields of Canada and the Dakotas that were created by the ancient sea that once covered half of North America. —Bella Jaramillo, RCC Assistant Director, Climate Justice

Bella Jaramillo is the co-lead of the RCC Coasts and Oceans program. She is a graduate of Florida State University and completing a Master's degree at Georgetown University. | | | | | | | | | | Members of the Audubon Society have addressed key members of Congress on this issue, we need to add to their momentum. Seabirds populations all over the world have declined precipitously by 70 percent over the last 70 years. Ocean temperatures continue to rise and make life harder for Atlantic Puffins nesting in Maine. Since 2021, only half the normal number of puffin chicks have survived. Urge your members of Congress to protect the

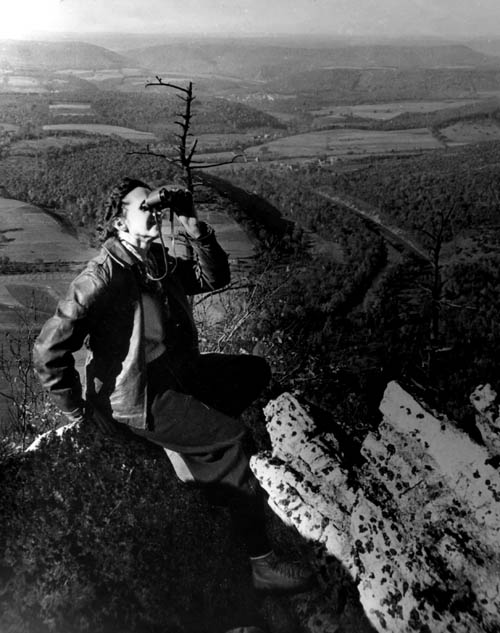

coastal habitats and fish that seabirds count on.  Many seabirds are in trouble due to shrinking food sources and habitat loss. Many species including the Atlantic Puffin rely on forage fish for food. These fish are the base of the ocean food chain and are threatened by climate change and human overfishing. This means seabirds don’t have enough to eat and habitats like wetlands, estuaries and mud flats are shrinking due to coastal development and climate change. Seabirds rely on these environments to rest during migration and forage for food. We must update the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act! This is our nation’s only federal fisheries law and it’s needed to protect the forage fish in the ocean that seabirds need to survive as well as protect seabirds from fishing gear entanglements and other fishing hazards.  | | | | | | RCC's President in Leading Scientists' Letter to Biden RCC President and CEO Dr. Robert K. Musil has joined over 100 prominent scientists in a formal letter to President Joe Biden and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland opposing proposed leases to open up coastal areas to offshore oil drilling. Musil, and other signatories organized by the non-profit, Oceana, stressed the harm to marine mammals and ecosystems, but especially the environmental justice impacts of such drilling which is often located near and disproportionately harmful to communities of color. | | | | | | | | As National Marine Sanctuary System Turns 50, Survey Finds Most U.S. Residents Want to Protect Ocean Ecosystems On Sunday, October 23, the National Marine Sanctuary System turned 50. Since its founding, the system has protected more than 620,000 square miles of ocean and Great Lakes waters in 15 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments. The National Marine Sanctuary Foundation has released a survey finding that U.S. residents across both political and geographic divides worry about the ocean. 83 percent of respondents saying the ocean is very or extremely important for marine life and habitats. | | | | | | | | Billions in Climate Deal Funding Could Help Protect U.S. Coastal Cities Communities across the country hope to tap into funds from Democrats’ new climate law to restore coastal habitats, part of a program that emphasizes nature-based solutions. Claire Arre, a marine biologist, waded through the sand in search of an Olympia oyster on a recent sunny afternoon, monitoring the bed her organization had built to clean up the surrounding watershed and contemplating all that could be done if she could get her hands on federal funding to expand the work. | | | | | | Hurricane Ian Was a Powerful Storm. Real Estate Developers Made it a Catastrophe. ‘Dredge-and-fill’ created thousands of homes vulnerable to storm surge. A century ago, the coast of southwest Florida was a maze of swamps and shoals, prone to frequent flooding and almost impossible to navigate by boat. These days, the region is home to more than 2 million people, and over the past decade it has ranked as one of the fastest-growing parts of the country. Many of those new homes sit mere feet from the ocean, surrounded by canals that flow to the Gulf of Mexico. | | | | | | Florida’s Fatal Attraction Everyone wants a piece of it. That’s the problem. Boats on roofs; cars out to sea; coastal towns underwater. The sand from Naples Beach now chokes Naples streets. Hurricane Ian’s 150-mph winds yanked houses off of their foundation in Fort Myers, a pretty town once known for its avenues of royal palms. As many as 50 people reportedly are dead in Florida. In some of our glossiest, most affluent, most densely populated communities, survivors now sift through the ruins of their slice of paradise. | | | | | | Climate Change Comes for the Freezers, a Key Tool for Alaska Natives Threatened by stronger storms and a melting permafrost, Indigenous Alaskans are grappling with how to keep the power running to their freezers, which store their traditional subsistence foods. As the remnants of Typhoon Merbok lashed the plywood walls of the house she shared with her children and grandchildren, Frieda Stone wrote a Bible verse on a small card. The severe weather, which hit Alaska’s western coast on Sept. 16, was the most powerful early-season storm scientists had ever measured there. | | | | | | Three Ways to Build Back Smarter After Hurricane Ian Big storms are becoming more common. That makes it crucial to take climate change into account when rebuilding. The damage from Hurricane Ian will very likely run into the tens of billions of dollars and scientists say the United States can expect more severe storms like it as the planet heats up. They also say the risks of increasingly wild weather make it all the more urgent that cities and states take steps to protect people and property. One of the ways to do that is to heed lessons and rebuild wisely after big storms. | | | | | | After Ian, Here’s What’s Next For Atlantic Hurricane Season A new disturbance headed toward the Caribbean has a medium chance to develop The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season is far from over. Even as former Hurricane Ian lost its tropical characteristics over the weekend in the Mid-Atlantic, its remnants stalled offshore leaving behind stormy weather that may not relent until midweek. Meanwhile, forecasters are closely tracking disturbances at risk of developing in the Caribbean and off the coast of Africa. | | | | | | | | Ocean Oil Pollution is Growing — and Not From Oil Spills Oil spills may be dramatic and devastating, but they’re not the biggest contributor to ocean oil pollution — not by a long shot. A report released Wednesday gives that distinction to fossil fuel runoff from highways, parking lots, and other land-based infrastructure, mostly transportation related. According to the report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Oil in the Sea,” these sources are by far the largest and fastest-growing contributor to ocean oil pollution. | | | | | | Hawaii to US Navy: Quit polluting Our Waters A $9 million fine and a sewage leak into Pearl Harbor are just the latest in a series of water crises. The U.S. Navy confirmed last week that 1,000 gallons of raw sewage leaked into Pearl Harbor near Honolulu, just two days after Hawaii’s Health Department fined the Navy nearly $9 million for hundreds of safety violations at the military wastewater treatment plant. At issue are not only the underground aquifers that supply drinking water for much of the island of Oahu, but also answerability by the military that has long had a contentious presence in Hawaii. | | | | | | | | A Better Solution to Florida’s Hurricane Problem Coral reefs can protect coastal cities from deadly floods, if only we keep them alive. Hurricane Ian was not just a powerful storm, but a preview of what’s to come. Climate change is helping cyclones intensify faster, produce greater storm surges, and dump more rain — all of which makes hurricanes more destructive and expensive. One early assessment for Ian indicates it cost as much as $40 billion in property damage. Engineers have long defended against the threat of hurricanes by building structures like levees and seawalls. Yet these tools are imperfect. | | | | | | Why Do Sharks Matter? Author Dr. David Shiffman Explains Dr. David Shiffman’s favorite thing to talk about are sharks, and has been since he was very young. “I’ve loved sharks for a really, really long time, since I was younger than anyone in this room,” Shiffman said to a few dozen last month at North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort. Shiffman, an interdisciplinary marine conservation biologist who specializes in the ecology and conservation of sharks, stopped in the Carteret County town as part of the tour for his book, “Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator.” | | | | | | | | Defining Terms: What Does ‘sustainable seafood’ Mean? The term “sustainable seafood” gets used a lot with regard to the fishing and aquaculture industries — it’s a phrase that varies in meaning and is used everywhere from policy directives to marketing strategies. But what does it really mean? Colloquially, the term “sustainable” is often in reference to environmental impact, with regard to overfishing and making sure that meeting human demands doesn’t destroy ocean ecosystems. | | | | | | Socially Sustainable Seafood Requires Diligence, Scrutiny In an undergraduate classroom at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in 2017, a group of students sat in front of a plate of sushi from a local restaurant. But it wasn’t lunchtime — the students were attempting to quantify how common the mislabeling of red snapper was across North Carolina. By analyzing the DNA from 43 fish samples they’d collected from seafood markets, grocery stores and restaurants across 10 counties, they found that a whopping 90.7% were mislabeled as red snapper. Most often, the substitutions were tilapia or vermillion snapper. | | | | | | | | Billions of Snow Crabs Have Disappeared From the Waters Around Alaska. Scientists Say Overfishing is Not the Cause The Alaska snow crab harvest has been canceled for the first time ever after billions of the crustaceans have disappeared from the cold, treacherous waters of the Bering Sea in recent years. The Alaska Board of Fisheries and North Pacific Fishery Management Council announced last week that the population of snow crab in the Bering Sea fell below the regulatory threshold to open up the fishery. | | | | | | | | | | | | Could Rachel Carson Have Imagined This Ocean? David Goodrich, A Voyage Across an Ancient Ocean: A Bicycle Journey through the Northern Dominion of Oil (Pegasus Books)  Sitting watching raptors migrate at Hawk Mountain in her stylish leather jacket with binoculars, Rachel Carson imagined the hawks, eagles, and falcons sailing on a sea of air. She also imagined how the limestone rocks on which she perched were formed beneath her in an ancient sea, millennia ago, as foraminifera and other minute calcium-laden creatures from the Silurian Period slowly piled up and turned to stone. Sitting watching raptors migrate at Hawk Mountain in her stylish leather jacket with binoculars, Rachel Carson imagined the hawks, eagles, and falcons sailing on a sea of air. She also imagined how the limestone rocks on which she perched were formed beneath her in an ancient sea, millennia ago, as foraminifera and other minute calcium-laden creatures from the Silurian Period slowly piled up and turned to stone.

Oil and gas were formed similarly in tar sands and shale formations eons ago in the Cretaceous Period from a huge inland prehistoric sea that once covered vast territory in what is now Alberta, Canada, and the Dakotas in the United States.

Rachel Carson with her knowledge of evolution, geology, and biology surely could have imagined the primeval days when tar sands and shale were formed. But could she have imagined the blasted moonscapes, the endless flames and flares, the ruined territory that once enticed Teddy Roosevelt? Rachel Carson with her knowledge of evolution, geology, and biology surely could have imagined the primeval days when tar sands and shale were formed. But could she have imagined the blasted moonscapes, the endless flames and flares, the ruined territory that once enticed Teddy Roosevelt?

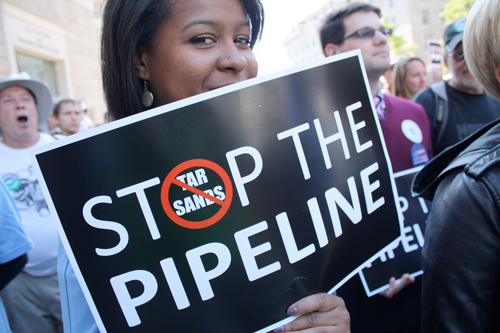

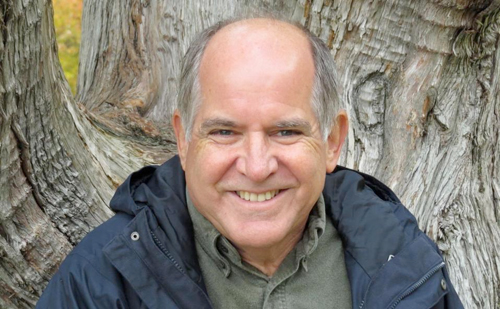

Environmentalists know these places mainly as placards and slogans. Stop the Keystone XL Pipeline! No Tar Sands Oil! It is hard to talk to others in the short-hand certainty of protest signs. Who can imagine what tar sands look like, where they come from, what will occur as this vast reservoir of oil and gas is pumped and burned for energy? David Goodrich can. He has ridden across this center of oil production and fracking alone for 1200 miles in cold and wind and rain on his old reliable bicycle, a Trek. Environmentalists know these places mainly as placards and slogans. Stop the Keystone XL Pipeline! No Tar Sands Oil! It is hard to talk to others in the short-hand certainty of protest signs. Who can imagine what tar sands look like, where they come from, what will occur as this vast reservoir of oil and gas is pumped and burned for energy? David Goodrich can. He has ridden across this center of oil production and fracking alone for 1200 miles in cold and wind and rain on his old reliable bicycle, a Trek.  David Goodrich is the kind of guy everybody likes to talk to – friendly, reasonable, great sense of humor, a raconteur who never bores you, and, maybe best of all, if he disagrees with you, he is not judgmental. You can invite him to dinner, or to Thanksgiving, and not worry that he will piss off Uncle George, the family know-nothing. David Goodrich is the kind of guy everybody likes to talk to – friendly, reasonable, great sense of humor, a raconteur who never bores you, and, maybe best of all, if he disagrees with you, he is not judgmental. You can invite him to dinner, or to Thanksgiving, and not worry that he will piss off Uncle George, the family know-nothing.

His latest book -- an incredible marathon bicycle trip to see where the United States’ treasure trove of oil and gas that is giving us energy independence while destroying the climate and the landscape is coming from – is what you have been looking for. A Voyage Across an Ancient Ocean is ideal as a holiday present for those friends and relatives with whom you don’t talk politics, and certainly not about climate change. Instead, let them instead spend weeks on a bicycle and at truck stops, diners, and small-town shops with David Goodrich and the oil drillers, cowboys, waitresses, and assorted Red state denizens he encounters and befriends along the way. His latest book -- an incredible marathon bicycle trip to see where the United States’ treasure trove of oil and gas that is giving us energy independence while destroying the climate and the landscape is coming from – is what you have been looking for. A Voyage Across an Ancient Ocean is ideal as a holiday present for those friends and relatives with whom you don’t talk politics, and certainly not about climate change. Instead, let them instead spend weeks on a bicycle and at truck stops, diners, and small-town shops with David Goodrich and the oil drillers, cowboys, waitresses, and assorted Red state denizens he encounters and befriends along the way.

Goodrich is as unassuming as he is genial. He never flashes credentials or talks down to the folks he meets, even though he is the former head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Observations and Monitoring Program and served as the Director of the UN Global Climate Observing System in Geneva, Switzerland. Like Rachel Carson, whom he admires, Goodrich has all the best science at his fingertips, but instead of drowning us in abstractions and arcane language, he writes like a journalist with a flair for conversation and description. He believes that if those who meet him, or read his book, could share his bicycle-level view and simply see and feel what has become of the Bakken, the huge oil and gas rich lands that were once an ancient sea, there would be no need to argue, to fall into well-rehearsed, defensive battle positions. Take Bryan, an oil driller who takes Goodrich out to see reclaimed land after the tar sands have been squeezed of their oil. Bryan admits the low, patchy green growth is about as good as you could expect. He thinks someday it will look better. But later, he emails Goodrich and says, given the need for jobs, for paying bills, “we’re all just pretty much caught between a rock and a hard place.” This confession of sorts is not the birth of a climate activist. But it is a beginning of possibly finding a way forward, even between an oil driller and a climate scientist.  So open and friendly is Goodrich that he gets shown the oil fields from the air by a guy named Matt, and meets with firefighters who have lost the battle to save huge swaths of land and homes to the “Beast,” a huge 2016 climate-stimulated wildfire in Fort McMurray. The picture Goodrich paints of blackened stumps needs no label as Dante’s Inferno, or climate hell. But we also feel the loss and tragedy for those who live and work there. So open and friendly is Goodrich that he gets shown the oil fields from the air by a guy named Matt, and meets with firefighters who have lost the battle to save huge swaths of land and homes to the “Beast,” a huge 2016 climate-stimulated wildfire in Fort McMurray. The picture Goodrich paints of blackened stumps needs no label as Dante’s Inferno, or climate hell. But we also feel the loss and tragedy for those who live and work there.

Goodrich also brings to life environmentalists, Indigenous protesters, and more. They are no longer the stuff of stereotypes, of placard slogans, or brief photos in the very back pages of the news. When he does offers brief, simple explanations of climate science or politics, they are surrounded by colorful characters, biking adventures that make you ache, and amusing stories like the colorful, look-a-like actors who play Teddy Roosevelt and his family down to the citified ranch clothes, and the spirited, bully East Coast accents. So, rush to give holiday presents of A Voyage Across an Ancient Sea. Tell your Uncle George you’re getting him a bicycling adventure, or a history of the Badlands, or a funny, colorful travelogue out West. Or, if your relative is mildly conservationist and outdoorsy and likes good writing, tell her you’ve found a new kind of Rachel Carson and a story about an ancient sea. They will see and hear and feel things they never imagined. —Bob Musil | | | |  Bob Musil is the President & CEO of the Rachel Carson Council and author of Hope for a Heated Planet: How Americans Are Fighting Global Climate Change and Building a Better Future (Rutgers Press). He rides his Trek along the much tamer C&O Canal and co-leads the RCC Coasts and Ocean Program with RCC Assistant Director, Bella Jaramillo. Bob Musil is the President & CEO of the Rachel Carson Council and author of Hope for a Heated Planet: How Americans Are Fighting Global Climate Change and Building a Better Future (Rutgers Press). He rides his Trek along the much tamer C&O Canal and co-leads the RCC Coasts and Ocean Program with RCC Assistant Director, Bella Jaramillo. | | | | | |  The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. The Rachel Carson Council Depends on Tax-deductible Gifts From Concerned Individuals Like You. Please Help If You can. | | | | | | | |  Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. Sign Up Here to Receive the RCC E-News and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts. | | | | | | | | | | | |